Niberca Polo, Associate Teaching Professor, Parsons School of Design, The New School

In the past twenty years, we have seen an exponential growth of virtual environments that have made collaborations across borders possible. Younger generations have grown-up immersed in these environments, which has led to the expectation that ‐ due to their ‘digital-nativeness’ ‐ they thrive in virtual spaces. However, this social construct can be misleading and has proven wrong in recent years, making it a significant source of anxiety in e-learning. Using a hybrid course called ‘PORTFOLIO’ as a case study, this paper addresses the ways in which a Learning Portfolio based course framework can be integrated into e-practices in order to negotiate such anxieties and, ultimately, nurture more cosmopolitan attitudes to the digital world, which the Cambridge dictionary defines as having experience of many different places and things (Audi, 2015)

digital cosmopolitan; Learning Portfolio; open-source technologies; peer-to-peer learning; soft technologies; virtual spaces

The rapid growth of technologies and global spheres in recent years has propelled virtual environments, reaching potentials that propel them beyond passive information exchange, such as informative websites or search engines. These new, fertile e-learning spaces ‐ including social media outlets, online software, games and Learning Management Systems (LMS) ‐ are full of potential for facilitating socially just interactions or fostering cultures of inclusion. These spaces build diverse communities, open-up access or accessibility and develop digital literacy in expansive networks; enabling negotiations of social interactions that enrich the learning experience of diverse groups who also constantly learn from each other by encountering different cultures and ideologies.

Such spaces stimulate a vast variety of perspectives, media outlets and diverse practices ‐ using soft (‘a view of technology grounded in the social sciences, and focuses on the material world as a world of experiences, emotions, and ideologies [...] humans become the drivers of the tools’ (Edwards et al., 2015, p. 235)) and open-source (free technologies available for trade) technologies, collaborations, peer learning, and crowdsourcing ‐ to amplify a multiplicity of voices. However, within this multiplicity the social constructs surrounding ‘digital natives’ ‐ also referred to as the N-[for Net]-gen or D-[for digital]-gen ‐ and ‘digital immigrants’ (Prensky, 2001; 2009; 2010; cited in Zuckerman, 2013) continue to persist. They hinder e-learning experiences, as these constructs set learning on a route to failure from the beginning. For ‘natives’ an expectation of ‘success’ is created through the illusion of familiarity, a presumption that students know the tools; for ‘immigrants’ there is the challenge to understand tools that are assumed to be foreign to them hence perceived as un-learnable. In either native or immigrant camp, anxiety builds from the onset, as students struggle to conform to these constructs, which simplify complex needs and capabilities. Alternatively, the challenge for newcomers is to learn in virtual environments where they are expected to thrive.

When we designed the PORTFOLIO course described here, this digital native-immigrant fallacy became evident, indicating that ‘digital nativism’ is not age-defined but rather, relates to the quantity and quality of exposure to and engagement with technologies, alongside individual motivation and personal drive. Engagement and ‘success’ is a matter of becoming a ‘resident’ instead of a transient ‘visitor’ (White and Le Cornu, 2011). This hybrid course explored the ways in which a ‘Learning Portfolio’ framework can be integrated into e-practices in order to negotiate these anxieties.

Another source of anxiety comes from feeling a loss of control that stems from engaging with technology, of negotiating privacy issues, constant public exposure and the weight of an everlasting digital footprint. These anxieties of engagement are, to a certain extent, the result of being consumers rather than the producers of content and of the technologies that shape and re-shape our online selves. Due to the geographical borderlessness in the current globalised world, becoming a responsible digital citizen ‐ a digital cosmopolitan ‐ is paramount to thriving and lowering some of the anxiety that is built from both internal and external sources. For this reason, the PORTFOLIO course aimed to foster a culture of cosmopolitanism (Appiah, 2010) where students could recognise the value of gaining insight from others and the importance of sharing personal opinions with respect. This cosmopolitan digital citizen has a responsibility towards the world at large and is open to a multiplicity of points of view.

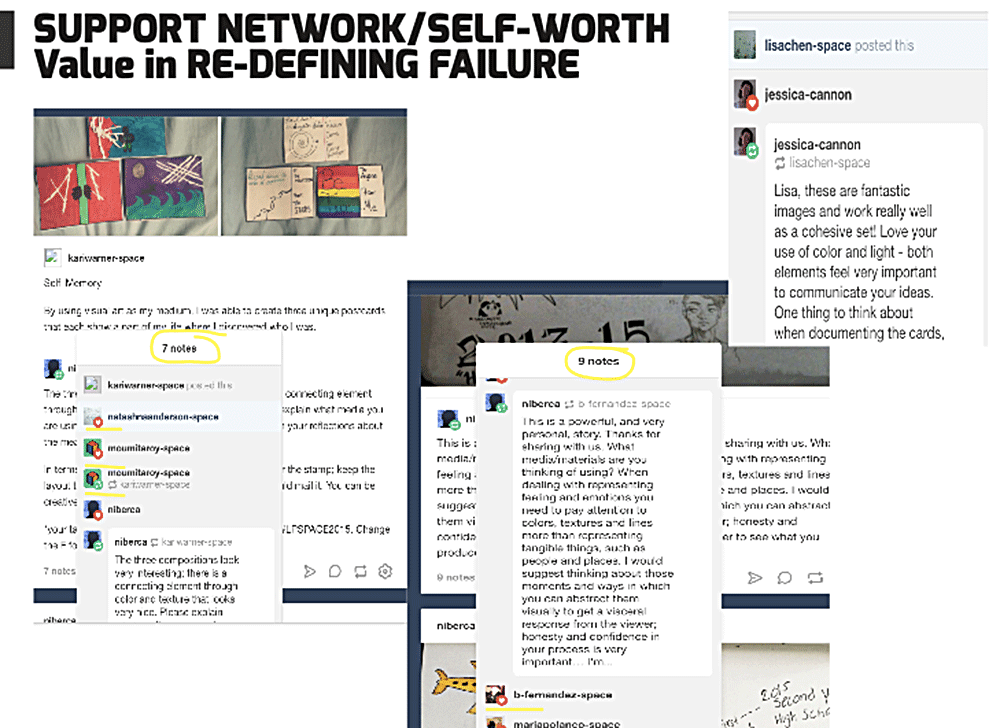

Learning Portfolios are online platforms ‐ a blend between blog platforms and journal (diary) writing ‐ that document the user’s history, providing tangible proof of learnt skills and competencies. As a practice, they redefine perceptions of ‘failure’ according to a learning curve rather than as meaning ‘lack of success’. They foster growth mindsets that empower learners to imagine their possible futures and design pathways to achieving them using intrinsic motivations as ways of experiencing feelings of success, thereby enabling learners to achieve short-term goals and foresee long-term aims as attainable (Dweck, 2010). A Learning Portfolio as a framework encompasses, at its core, self-reflective practice based on the premise that through documenting their process, self-reflection, final productions and by constantly sharing them with a growing network of peers, learners become more aware of their individual growth, gain exposure and become part of a dynamic learning system.

PORTFOLIO was a free hybrid (online/onsite) pilot course for underserved high school students from NYC, offered by Parsons SPACE Pre-College Academy at The New School. During the Fall term of 2015, the four-month course followed a Learning Portfolio framework, in which learners were exposed to both design theory and digital tools, which guided them in producing a portfolio that was then used to apply to art and design courses at university level. Our aim was to foster collaboration and knowledge-sharing; to build a community driven by common interests both in and out of the virtual space; to create meaningful networks; and to expand access and accessibility for underserved populations. The 18 students who took part were a poll of various ethnicities ‐ of mostly minority groups ‐ who had after-school jobs and other responsibilities within their family structure; hence a need for flexibility. An online course allowed students to manage their schedules more efficiently. We also met in person 3 times (for 3 hours each time) at Parsons: first to meet the group, then to share techniques on documenting process and finally at the end of the semester, when students shared their final Learning Portfolios with friends, family and our community.

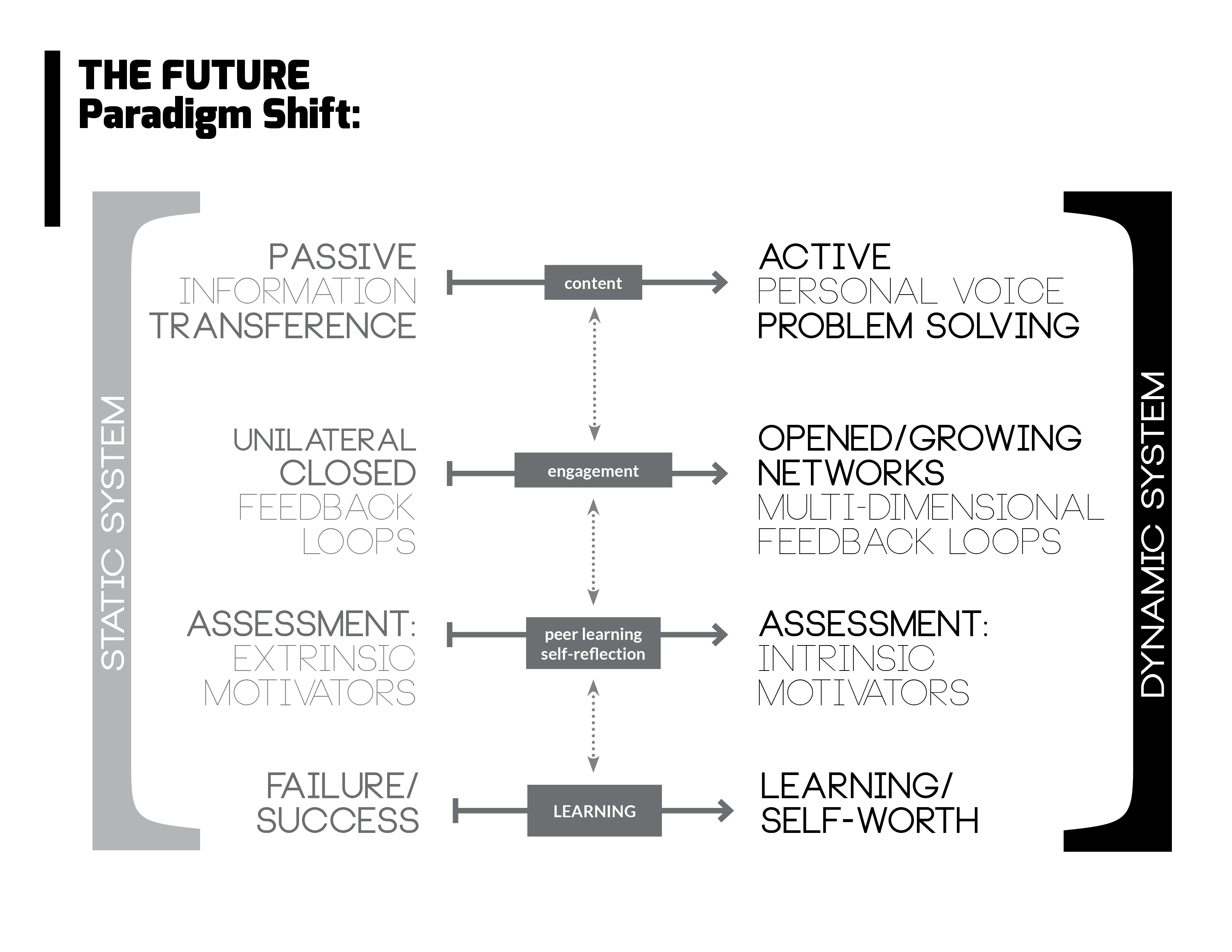

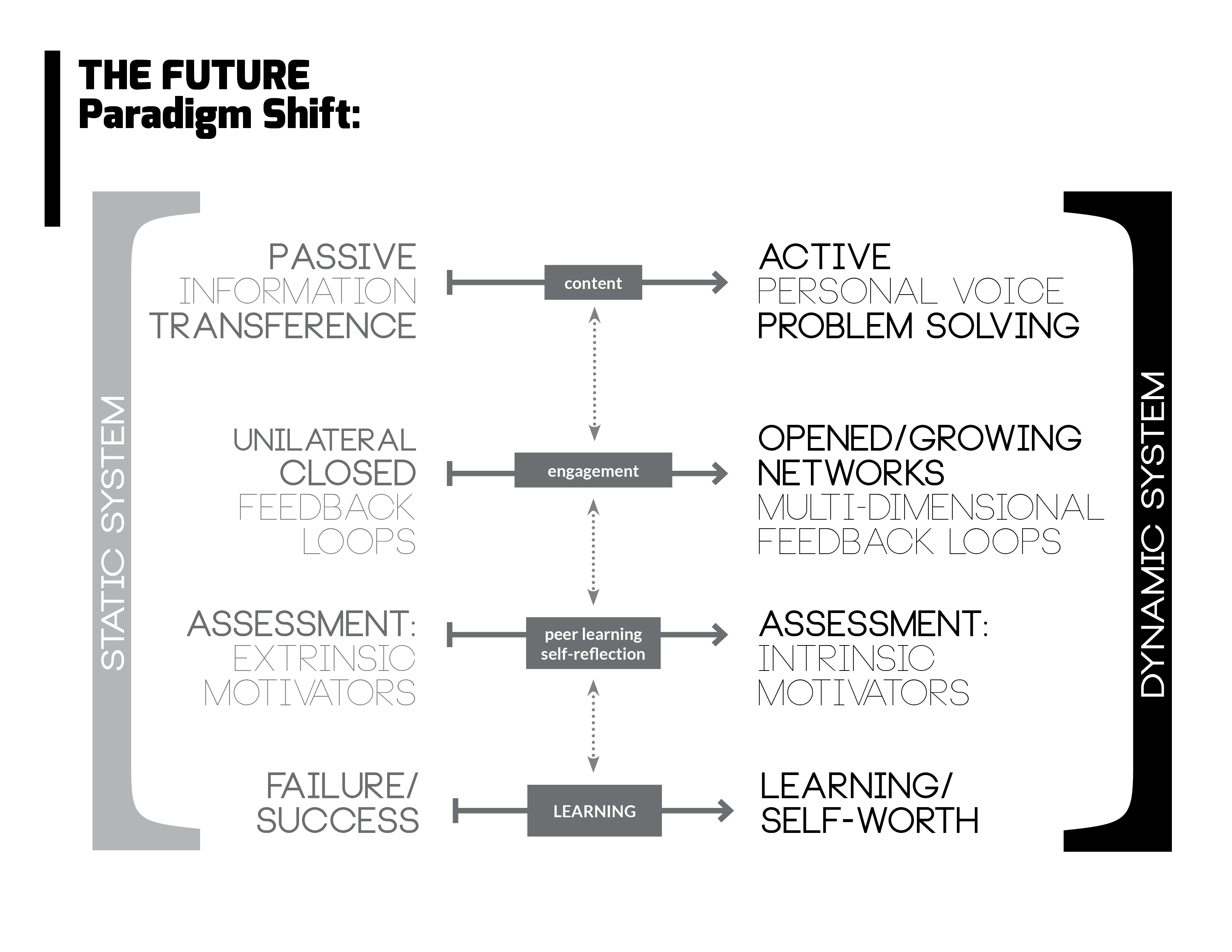

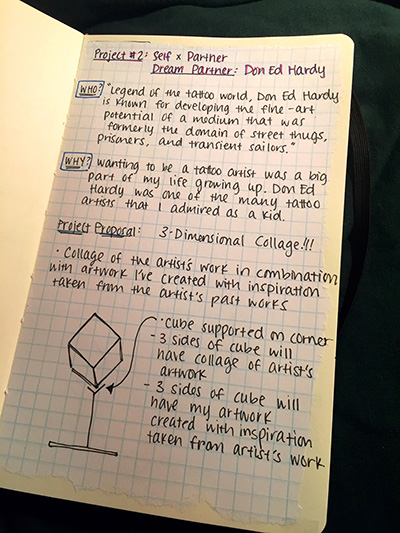

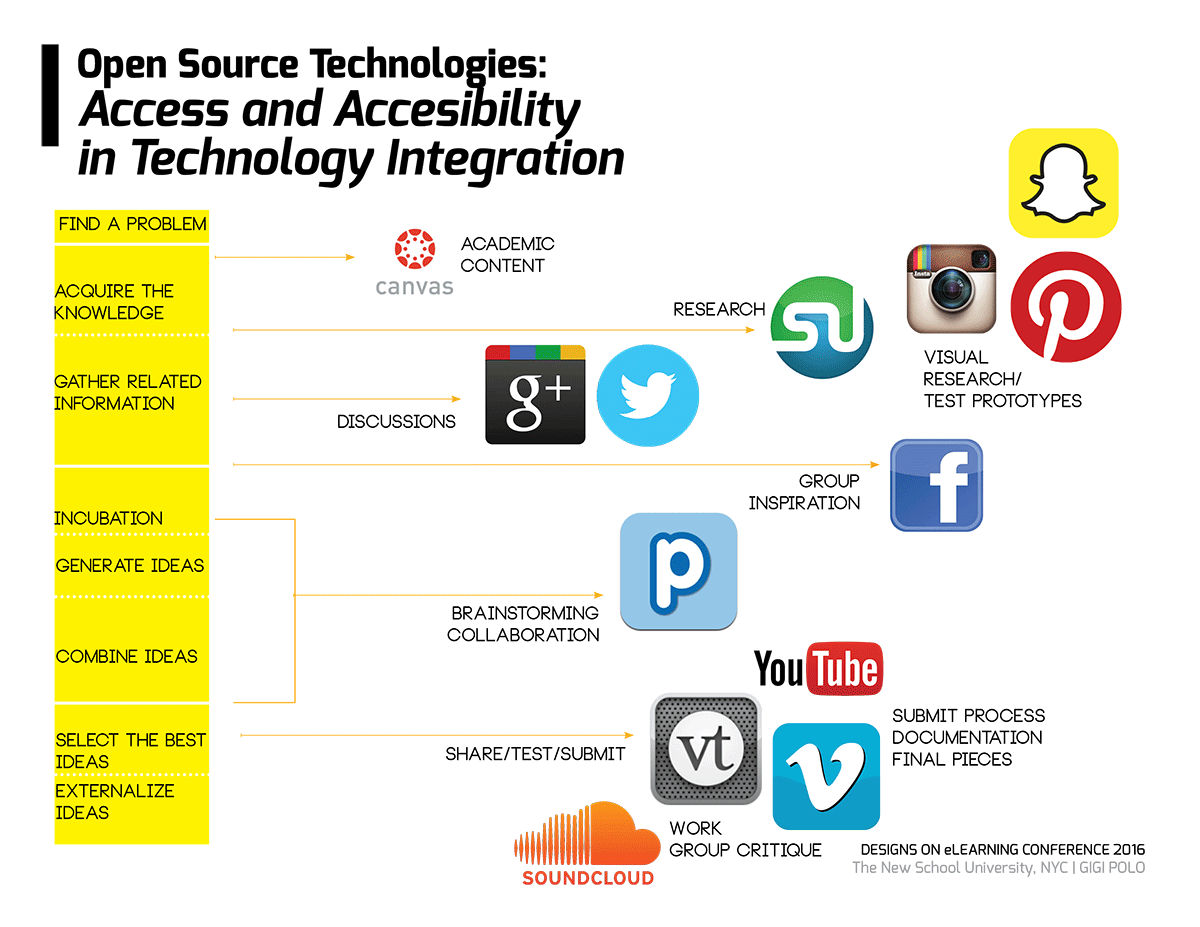

One of the main objectives was to entice students to produce original works, in order to shift their mindset from passive receivers (consumers) to active producers in virtual spaces. Based on a series of design assignments that students submitted to specific deadlines, we used Tumblr (tumblr.com) as a platform for teaching; proving assignment briefs, support content, inspiration and tutorials amongst other tasks. Students received group feedback and posted assignments using their personal Learning Portfolios, which were hosted on Tumblr in order to engage in larger conversations with communities beyond the ‘classroom’. Based on comments gathered during the application process, we decided to use Tumblr as applicants expressed eagerness to become part of a network of like-minded people, an opportunity not afforded by their day-to-day lives and many responsibilities. When assessing and grading students, we concentrated on self-assessment as communicated by self-reflections, peer-to-peer feedback and perceived relevance from others engaged in the opened Tumblr network based on likes, re-blogs, and comments. It is important to note that, even though students needed to apply to join the program, previous knowledge or exposure to design or digital tools was not required. Implementing a project-based methodology, we structured assignments as follows (Figure 2):

Within the course, tensions arose from social misconstructions that students were ‘digital natives’ (N-gen). This terminology was inapplicable since it contrasted with the realities of these learners, who had largely experienced lack of access and narrow exposure to digital environments. Some students were technically savvy while others felt lost and powerless in a digital environment. In initial conversations, students expressed concerns that were unrelated to the platform itself and more geared towards internal and external stress or the required levels of engagement with the platform, the sociality of becoming a digital resident. As the course progressed, students voiced very real anxieties due to external pressures, primarily a lack of support systems and facilities ‐ namely no financial and/or emotional family support and no computer access. Internal forces also heightened anxiety, for example when students struggled to reconcile people’s expectations with their own realities and desires. In a survey conducted during the mid-semester check-in, one of our students expressed that prior to the course she had experienced low exposure to digital environments, but that learning to navigate the digital tools gave her a sense of agency. More importantly, students’ eagerness to be heard, be relevant and feel a sense of belonging in both their community and the wider world, brought to the surface conversations that regarded personal voice, identity and social responsibility in virtual spaces.

Following a project-based methodology, we introduced students to digital technologies and they became producers of new knowledge ‐ of their own narratives ‐ rather than consumers of content. Students understood technologies as tools that they could use and appropriate. In order to develop their assignments, they learnt about the ways in which those tools could be transformed, adapted and inscribed.

As Chip Bruce and Maureen Hogan explain in their chapter on ‘The Disappearance of Technology’ (Bruce, 1998, as cited by Zuckerman, 2013, p.141), to avoid being controlled by external trades of consumption and instead, shape identities from within, tools need to eventually become ‘invisible’. Using this approach of introducing digital tools but also making them invisible, we tapped into students’ everyday creativity by encouraging ‘wandering’ and ‘serendipitous’ exploration (Richards, 2010). As can be seen from Figures 3 to 5 above, we encouraged students to use Tumblr as a medium for knowledge production. Open-source technology and social media enrich the learning experience by sharing, testing, and assessing growth.

Giving students agency is paramount to their learning experience and in developing their sense of self. It is especially important in nurturing ‘digital cosmopolitans’ ‐ those who carry themselves with ethics, responsibility, transparency and abide by a moral code when functioning in the digital world. While learning new technologies as part of the PORTFOLIO course, students not only developed concepts relevant to their lives and interests, they also needed to find ways to express their opinion with honesty and respect. They had to create a form of curated-self, which was professional yet genuine. We also observed how, when students create virtual identities from a place of empowerment ‐ as a subject with agency, as opposed to a powerless object ‐ their work propels a culture of digital citizenship, of cosmopolitanism (Appiah, 2010). Through self-reflection, students were able to share their fears, challenges, learning experiences and solutions. By acting as ‘residents’ of the virtual space, with time devoted to learning and active engagement, our students were able to open-up, lower their anxiety and thrive in this virtual space. The more their online networks expanded ‐ by seeing their work re-blogged, gathering ‘likes’ and comments ‐ the higher the quality of their design outputs and self-reflections; they developed a critical eye and gained language awareness.

Open-source technology (the Tumblr platform) served as a way to expand networks beyond the virtual classroom and test productions in what psychologist Teresa Amabile calls ‘social appropriateness’ (1983). Tumblr acted as a way to find a sense of accomplishment and of self-worth as well as social validation because students found a space in the world where their voices were heard. Rather than using these open-source platforms as content-dumps, they were niches in which students explored their professional interests through digital literacy and engaging interactions and those explorations built supportive networks, a form of virtual proximity, of a sense of belonging to a complex network while feeling closer and more connected to others. In the words of Amabile, if ‘experts from a domain come to a consensus, it means the product is appropriate in that domain [...]. Appropriateness is defined by social groups, and it’s culturally and historically determined’ (Amabile, 1983, p.1010).

Looking at our retention rate, one of the major obstacles for this group was a struggle to meet deadlines. One change that might address this would be to re-structure the course as a self-paced space, thus catering to students varied individual needs. Out of the 18 students in the course, 4 completed all assignments, 10 partially completed the program with one or two submissions and 4 dropped out over the course of the semester with no completed submissions. Of the 4 students who completed the program, 2 have continued developing their Learning Portfolios, including works created in art and design school/afterschool programs.

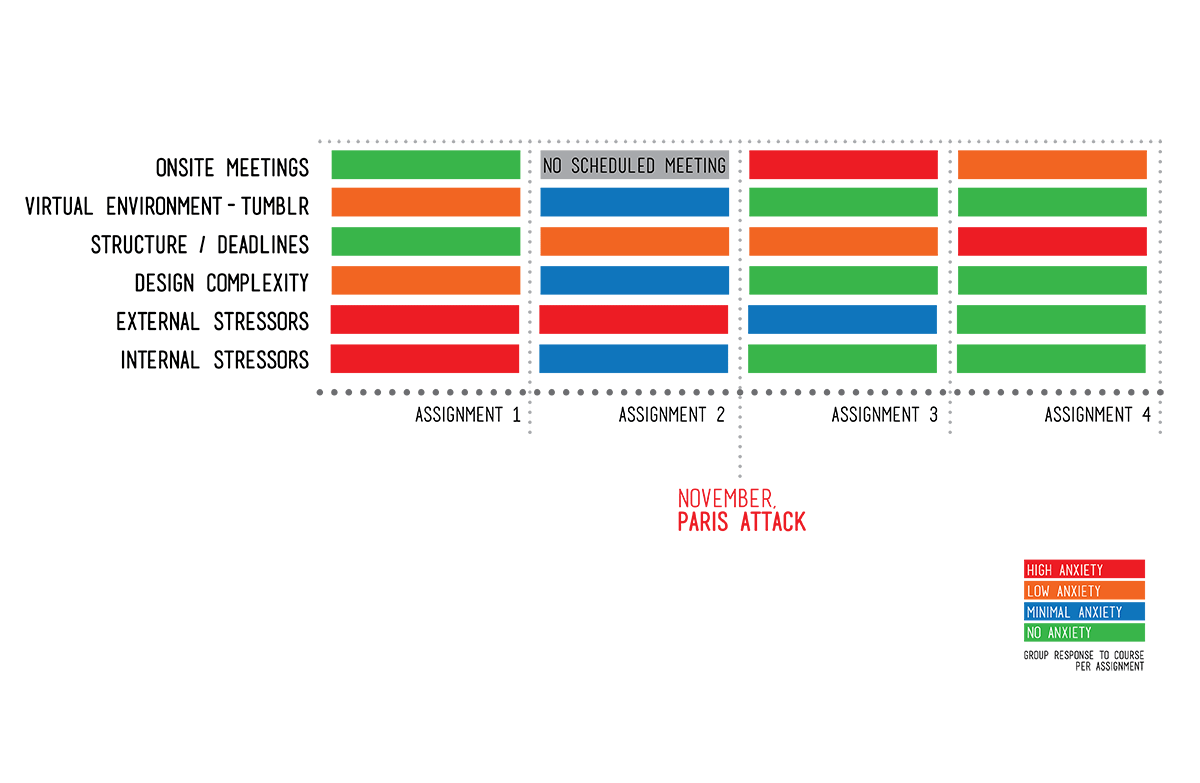

As shown in Figure 10, the anxiety produced by internal and external stressors lowered in the second half of the course; we attribute this drop to students having the ability to share their documented history ‐ including interactions with their Tumblr network ‐ to their families and friends as a way to give them an inside look into their passion and career aspirations. Also, students demonstrated acquired knowledge in design production and writing skills in their self-reflections and peer reviews, and an overall familiarity ‐ and for some, a level of mastery ‐ in managing and navigating Tumblr.

Another issue we encountered was a very unfortunate, and unforeseen, event; on Friday, November 13, 2015, the Paris terrorist attacked shook the world, and had a strong effect in our city. We scheduled our second meet-up to be on Saturday, November 14 and only 8 students attended because of a general fear of what could happen in New York, in comparison to our first meeting, at which all 18 students were in attendance. This unpredictable event showed us the value of online learning environments; students who stayed home were still able to access materials on their own time in order to follow the workshop structure independently and we also documented the workshop to showcase examples of good documentation practices. Overall, we feel that in this specific group of students, anxieties were directly related to levels of digital literacy and internal and external forces that had an effect in the ways in which they used and behaved in the virtual space.

A lesson I learned from my grandfather who, aged 82, decided to learn how to use a computer in order to catch up with his future was, ‘to live in the present is to prepare for an uncertain future’.

At the beginning of the PORTFOLIO course, students struggled with the transition from being digital visitors to residents, but they did, however, show active engagement when they immersed themselves as ‘total residents’ of the virtual space (White and Le Cornu, 2013). Moving forward, we need to revisit the structure of the course and take into account students’ individual needs and struggles, addressing issues related to time commitments, accessibility, and access. Possible revisions could include:

In adapting the revisions aforementioned, we seek to achieve two of our set goals: to cater to students’ individual needs and to guide them to building pathways for success in line with their aspired futures. We see great potential in adapting the PORTFOLIO model as a way to foster virtual spaces that serve as conduit towards learners’ digital literacy and responsible practices in virtual spaces. As seen in our results, PORTFOLIO is a model that nurtures sociality in the virtual landscape — a form of virtual proximity, where learners, by interacting with people around the world, can feel more connected, build empathy and nurture relations across borders. Moreover, it is a recorded history, one to which learners can look back in order to assess their growth, and carry this practice over from educational institutions into their professional lives.

Virtual environments provide an accessibility that is reduced in onsite courses, in terms of providing more flexibility to time constraints, eliminating commuting expenses and challenging mobility due to physical disabilities. Moreover, it is ideal for populations abroad ‐ both national and international ‐ who may be eager to build skills that help them expand their career opportunities but are unable to leave their hometowns.

Although our anxiety in virtual spaces comes from real threats, we cannot be oblivious of the dangers we are exposed to in our daily life, when we commute, travel, and engage in face-to-face activities. As in the example of the Paris attack of 2015, we have to recognize that danger is everywhere, and it touches us in some many ways. Consequently, it is important to recognize that issues of consumption, privacy, free labour, identity theft and impersonation, to name but a few, are real dangers in open virtual spaces and that people of all ages engage in online practices every day. We all fear the unknown and these worries are real but this fear also facilitates a culture of technology consumption, of passive acceptance. Instead, we need to acknowledge these dangers and provide brave environments in which learners ‐ of all ages ‐ act as digital cosmopolitans of the world (Appiah, 2010), establish spaces that redefine failure as a formative building block process and foster meaningful interactions, each of which prepares us for the uncertainties of the future.

Amabile, T. M. (1983) ‘The social psychology of creativity: a componential conceptualization’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(2), pp.357‐377. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.45.2.357.

Audi, R, (ed.) (2015) The Cambridge dictionary of philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Appiah, K. A. (2010) Cosmopolitanism: ethics in a world of strangers. Callifornia: Paw Prints.

Bruce, B. C. and Hogan, M. P. (1998) ‘The disappearance of technology: toward an ecological model of literacy’ in Reinking, D., McKenna, M. C., Labbo, L. D. and Kieffer, R. D. (eds.) Handbook of literacy and technology: transformations in a post-typographic world. Florence, KY: Routledge, pp.269‐281.

Dweck, C. S. (2009) ‘Mindsets: developing talent through a growth mindset’, Olympic Coach, 21(1), pp.4‐7.

Dweck, C. S. (2010) ‘Even geniuses work hard’, Educational Leadership, 68(1), pp.16‐20. Available at: http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/sept10/vol68/num01/Even-Geniuses-Work-Hard.aspx (Accessed: 27 February 2017).

Edwards, C. (ed.) (2015) The Bloomsbury encyclopedia of design. London, New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Learning Portfolio Space (2016) ‘About us’, Tumblr. Available at: http://learningportfoliospace.tumblr.com/aboutus (Accessed: 10 January 2017).

Prensky, M. (2010) Teaching digital natives: partnering for real learning. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press.

Prensky, M. (2009) ‘H. sapiens digital: from digital immigrants and digital natives to digital wisdom’, Innovate Journal of Online Education, 5(3), pp.1–11. Available at: http://nsuworks.nova.edu/innovate/vol5/iss3/1/ (Accessed: 27 February 2017).

Prensky, M. (2001) ‘Digital natives, digital immigrants part 1’, On the horizon, 9(5), pp.1‐6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/10748120110424816.

Richards, R. (2010) ‘Everyday creativity’ in Kaufman, J. C. and Sternberg, R. J. (eds.) The Cambridge handbook of creativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.189‐215.

Sawyer, R. K. (2011) Explaining creativity: the science of human innovation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

White, D. S. and Le Cornu, A. (2011) ‘Visitors and residents: a new typology for online engagement’, First Monday, 16(9). http://dx.doi.org/10.5210/fm.v16i9.3171.

Zuckerman, E. (2013) Rewire: digital cosmopolitans in the age of connection. New York: WW Norton & Company.

Niberca Polo is a Parsons graduate from the Communication Design Department. She launched her Graphic Design studio Myellow Boots in 2005. Niberca is engaged in Social Justice activism, currently acting as Faculty co-chair of The New School Social Justice Committee, and as part of the advisory board of CVSA, a non-profit organization that organizes volunteers. Niberca teaches Art and Design at Parsons School of Design, The New School and at CUNY, College of Staten Island (CSI). She was one of the coordinators of the Digital Learning Portfolios project at Parsons SPACE Pre-College Academy, and served as Learning Portfolio Specialist at Carnegie Hall Educational Programs.