Hannah Breslin, Student Employability Practitioner, Careers and Employability, Teaching and Learning Exchange

This article focuses on understanding the challenges students face when identifying and articulating their skills. Situated within the context of Careers and Employability, it explores how students can identify and articulate their learning when accessing professional and creative opportunities beyond university. It describes activities that consisted of desk research and action research, with the former focusing on a literature review in the field of career development. The small-scale action research phase consisted of three activities (an online pre-workshop questionnaire, a two-hour seminar-style workshop and a paper-based, post-workshop questionnaire) resulting in several firm conclusions about the challenges students face when identifying their skills. This action research also provided an insight into how students can be supported to overcome these challenges. These findings feed into the delivery of a new skills audit exercise, designed to encourage students to author unique and discipline-specific skills profiles.

employability; skills; attributes; knowledge; professional development; skills audit

Part of the Teaching and Learning Exchange, Careers and Employability is UAL's dedicated careers and enterprise service, providing support to students and helping them embark on professional futures in the creative industries (UAL, 2016a). In my role as a Student Employability Practitioner, I work with students and graduates from all levels of study and disciplines across UAL’s six colleges. For the purpose of brevity, this article will henceforth simply refer to ‘students’ throughout, though a number of graduates also took part in this research.

The day-to-day job of a Student Employability Practitioner involves delivering a range of extra- and co-curricular workshops. I support students with all aspects of their professional development and central to much of what I do, is helping them identify and articulate the depth and value of the learning experience offered by their course. Workshops cover topics such as ‘CV Writing’, ‘Job Hunting’ and ‘Career Planning’. Students from across UAL can attend our extra-curricular sessions, while the co-curricular sessions are usually run for students on a particular course or pathway. All workshops are optional and non-assessed.

Working on the edges of the core curriculum in this way, presents a range of challenges - but this position also gives me a unique vantage point from which to observe themes or patterns that occur across diverse student groups. One such over-arching issue I have observed when facilitating these workshops is that students often struggle to identify their skills. In the context of this research, I define the word ‘skills’ in relation to employability and use it as shorthand for skills, knowledge and attributes. This choice is supported by a widely accepted definition of employability skills as a set of attributes, skills and knowledge that all labour market participants should possess (CBI/NUS, 2011, p.12).

Skills identification can be particularly challenging in relation to art and design, where a multitude of intangible or ‘soft’ skills are often developed alongside technical or ‘hard’ skills. The Creative Graduates Creative Futures report highlights that art, design, craft and media graduates struggle to communicate confidently about their skills, partly because much of their learning is implicit rather than explicit (Ball, Pollard and Stanley, 2009, p.65). I come across this frequently, when students proclaim they have ‘nothing’ to put on their CV or no ‘real’ experience to talk about at interview. A short, probing conversation will often reveal a multitude of skills and experience that the student had simply failed to reflect on or had taken for granted as commonplace and, therefore, inconsequential.

A UAL-specific report from 2008, noted that students lacked confidence in identifying and explaining their strengths and achievements, in making a connection between what they have learned and where they might fit in in the world of work (Ball, 2008). Other notable research demonstrates that this is a longstanding issue, with Blackwell and Harvey expressing concern that art and design graduates are unaware that they are well placed to succeed in the graduate recruitment market (cited in Ball, Pollard and Stanley, 2009, p.65). A number of other recent HEA-funded research projects, which focus on enterprise and employability skills, confirm that this is an on-going area of concern (Roth, 2015; Sant, 2013). In particular, Roth notes that students do not always know what they offer as practitioners and as a result, maintain the perception of feeling unprepared for their future and unsure about their career prospects (Roth, 2015, Slide 7).

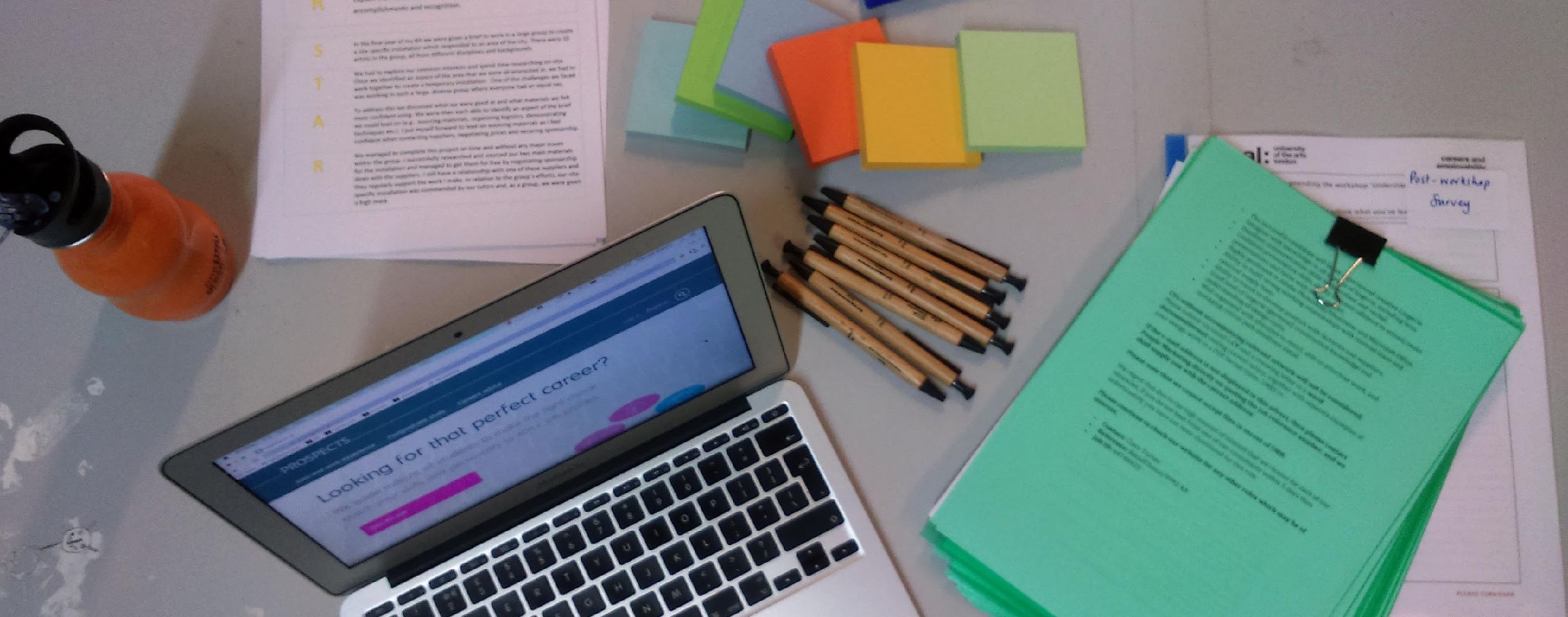

Tied up in this desire to explore why students find the task of identifying their skills challenging, was my frustration with the current solution used by Careers and Employability, which involves students completing a skills audit questionnaire (Figure 2). This questionnaire forms part of our department’s career-planning workshop - ‘CareerLAB’. I have inherited this questionnaire and struggle with the fact that it does not focus on any specific discipline and instead favours broad, transferable skills. Students need to be conversant with the language used in industry in order to fully articulate what they are capable of to potential employers, clients and collaborators. Our current skills questionnaire, with its focus on somewhat generic skills, overlooks the importance of identifying and articulating discipline-specific skills.

In the past, this questionnaire has been tailored for specific courses and disciplines, but this is time-consuming and ultimately unsustainable. My efforts also highlight one of the challenges of working outside the core curriculum - that I do not have the required insight to create truly discipline-specific lists of skills. No amount of independent research can equate to living and breathing a particular subject or industry. I can comfortably create a respectable skills audit questionnaire for fine art students, as this is where my own creative practice lies. However, the discipline of design and communication, where my first-hand experiences are limited, presents more of a challenge. This is a significant constraint that is inherent in the current format of our skills audit exercise. Ultimately a questionnaire-style skills audit will always be limited as it is defined by the knowledge and insights of the person who writes the questionnaire itself.

Additionally, completion of the audit as a tick-box questionnaire encourages students to focus on the quantity of skills they select (as opposed to relevance, value and so forth), which in turn provides an easy and unhelpful metric for them to judge their audit. During feedback sessions I have observed many instances of ‘comparing and despairing’ (Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust, 2016), in which students compare the number and range of skills their peers have ticked, against their own audit:, and see the good things about their peers and only the bad things about themselves. Indeed one workshop participant stated: ‘feelings of inadequacy within my peers, other people always seem to be generally more clever, wittier and ambitious than I’ (Participant A, Breslin, 2016a).

In addressing students’ hesitancy or lack of confidence when articulating their skills, I initially undertook desk-based reading and research. This desk research provided me with the context for the action research that followed. The action research consisted of three parts: an online pre-workshop questionnaire; a two-hour, face-to-face workshop; and completion of a paper-based post-workshop questionnaire.

Participants were recruited through two different channels - our monthly Careers and Employability newsletter and a direct email to all students who had previously attended one of the extra-curricular workshops. Our newsletter is optional, as is attendance at the extra-curricular workshops, so these recruitment methods resulted in convenience sampling with a bias towards students who are already inclined to seek out the support of Careers and Employability. I felt comfortable with this bias, as this project aims to address an issue faced by individuals who are actively engaged in exploring their career options.

The number of students who registered was smaller than I had hoped, but encouragingly this small number nonetheless resulted in nine participants taking part in all three aspects of the research. The participants were diverse - coming from a variety of backgrounds, colleges, courses and levels of study. There was a good mix of undergraduate and postgraduate students, as well as a number of graduates. Four of UAL’s colleges were represented and participants came from divergent courses such as MA Strategic Fashion Marketing (London College of Fashion) and BA (Hons) Painting (Camberwell College of Arts).

Though cross-college representation was encouraging, it is worth noting that there was a lack of diversity in another respect - all participants were female. This is not unusual when we consider the wider context of Careers and Employability workshops, where the majority of attendees are consistently female. The method of recruiting participants also means that it is unsurprising that this gender bias was brought to bear. It is important to state that the outcomes and any proposed solutions of this research will be naturally biased towards a female audience.

A range of sources was consulted when developing the pre-workshop questionnaire (Hardy and Ford, 2014; Kember, 2000; Nijjar, 2009; Vagias, 2006). This ensured that the structure and language would enable data to be gathered in an effective way.

The pre-workshop questionnaire featured two distinct parts. The first asked students to write down the skills they currently have. I did not seek to define ‘skills’ at this stage, as I was interested to see what students understood by this term without any prompts or guidance. Two questions followed in which participants were asked to rate how happy they were with their list of skills and how difficult they found it to complete this task. The second part of the questionnaire then asked participants to suggest up to three challenges they faced when identifying their own skills.

The workshop took place over two hours at Chelsea College of Arts in March 2016. It involved nine participants who completed a range of tasks including: discussion in pairs (of the challenges they faced when completing the pre-workshop skills audit); exploration of emerging themes and shared concerns; introduction to tools and resources (used to explore their unique skill sets); independent research time (allowing them to develop a revised skills list); and completion of the post-workshop questionnaire (taking into account workshop activities, which are outlined in more detail in Appendix 1).

While the focus of the research was to simply find out what challenges students face when identifying their skills, it became apparent that the pre-workshop questionnaire gave me an insight into how I could tentatively explore solutions at this stage. As a result, two sections of the workshop were dedicated to supporting students to overcome some of these challenges (see Appendix 1).

The post-workshop questionnaire was designed and mapped onto the pre-workshop questionnaire in order to encourage ‘ipsative’ self-assessment. This model of assessment is based on a learner’s previous work rather than on performance against external criteria and standards. Significantly an ipsative model of assessment encourages learners to work towards a personal best, rather than always competing against other students (Hughes, Okumoto and Wood, 2011, p.2). To further promote independent reflection, I gathered the paper-based post-workshop questionnaires and used ‘Wufoo’ (an online platform for building forms) to enter the data digitally after the workshop. This meant each participant received two emails - one that captured their responses to the pre-workshop questionnaire which they completed online. By manually entering the post-workshop questionnaires on to Wufoo, participants also received a second email that captured their responses to the post-workshop questionnaire.

The pre-workshop questionnaire, combined with discussions during the workshop, were the most effective tools in terms of answering my initial research question - what challenges do students face when identifying and articulating their skills?

During the workshop we explored if there were any shared concerns or common themes emerging from the pre-workshop questionnaire, through discussion in pairs. I made notes on Post-Its during this group discussion and placed them on a white board for participants to see. This enabled all of us to have an overview of the challenges discussed and to identify some key themes.

After the workshop I gathered these Post-Its and compared them with the data from the pre-workshop questionnaire. I then analysed the language used by participants and coded the data by indexing themes in relation to the challenges the participants identified (Appendix 2). Three priori themes were evident and are supported by my desk research. A fourth grounded theme emerged from analysing the data and, as such, was an unexpected finding.

Students frequently referenced feeling unconfident or ‘under’ confident when seeking to identify their skills. They talked about needing permission or some form of external validation to be ‘allowed’ to state they are skilled at something. They often used the word ‘strengths’ on a continuum with ‘weaknesses’ and during the group discussion there was a sense that students were more readily able to identify their perceived shortcomings or an absence of skills, rather than the skills they did have.

Several comments highlighted how students felt it was important to be an ‘expert’ at something before you can include it on your CV or discuss it with a potential employer/client. This is problematic because there was no one definition of what ‘expert’ meant. There were references to meeting certain standards, but again these standards seemed arbitrary. This highlights that students do not recognise that employers may not be looking for fully formed experts and that they will likely be expected to continue to grow and learn as they work professionally.

The task of listing their skills caused some students to question what the term ‘skills’ refers to. This is an understandable challenge in a world where words describing ‘skills’, ‘knowledge’, ‘experience’ and ‘attributes’ tend to be used interchangeably. We discussed how, in this instance, we were using ‘skills’ as shorthand to describe all of these facets and students commented that this was helpful in trying to think more laterally about what they are capable of. A number of students correctly pointed out that simply being able to list your skills is not sufficient and they benefitted from the part of the workshop dedicated to creating evidence-based examples of using their skills effectively.

Several students, particularly those who had significantly shifted the direction of their career/practice, expressed concern over having too many or unrelated skills. They found themselves unable to identify how a skill could transfer from one context to another. They felt that having a varied skill set suggested they were unfocused or not committed to a particular industry or career. They believed prospective employers or clients would view this negatively.

That confidence, or lack thereof, plays such a key role in students being able to identify their skills is unsurprising. This is supported by my research into this topic, as well as observations from my own teaching practice. Similarly, I often hear students state that they cannot include a certain skill on their CV because they do not consider themselves to be an ‘expert’. I am also aware, through a number of other sessions that I teach, that the way students define and articulate their skills is problematic.

What I was surprised by was that students consider a broad or varied skill set negatively. From my professional perspective, having a range of skills and experience in more than one industry is invaluable. This is a challenge I would not have expected students to identify.

While the indexing of these resulting themes supported me in answering the research question, there were some additional observations I made after reflecting on the pre- and post-workshop questionnaires, as well as my notes from the workshop. These additional observations give me an insight into the wider context of my research question and will support me when it comes to developing an appropriate teaching intervention going forward.

Many of the workshop participants rated the task of identifying their skills as either ‘neutral’ or ‘difficult’ in the pre-workshop questionnaire. No participants identified this task as easy or very easy. This was as expected, based on my previous desk research as well as the observations I have gathered through my own teaching practice.

In the post-workshop questionnaire the majority of participants rated the task of creating a list of their skills as easy or very easy. This is encouraging as it suggests I have identified the challenges students face and developed some methods they can use to overcome these challenges. Participants were asked to rate their ‘happiness’ with their skills list in the pre-workshop questionnaire. This question yielded a wider range of answers from participants - though the majority stated that they were only moderately happy with their list of skills at this stage. In the post-workshop questionnaire the majority of participants rated their level of happiness as ‘very’ or ‘extremely’ happy. Again this is encouraging and suggests the modest section of the workshop that tentatively explored solutions to the challenges faced, had an impact.

Despite finding the task of identifying their skills in the pre-workshop questionnaire challenging, each participant was nonetheless able to produce a list of skills. These lists varied in length, from the three skills listed by one participant to the fourteen skills listed by another. This was surprising as I assumed that if participants struggled with this task, it would follow that their lists would be limited in terms of the number of skills - however, this was not the case with all participants. I had assumed that the main difference between participants’ pre- and post- workshop lists would simply be numerical, with students listing more skills in the final post-workshop questionnaire. Yet the increase in the number of skills listed was not as significant as I had imagined. Indeed, in some cases, there was no increase at all. What I did observe was that participants articulated their skills much more effectively in the post-workshop questionnaire and that the skills detailed were closely linked to their discipline (see Figure 3). This is significant as it suggests that a student-focussed, research-led approach to completing a skills audit overcomes one of the problems inherent in our original tick-box questionnaire, which only detailed broad or transferable skills. This simple tactic enables me to overcome the challenge of not always having discipline-specific knowledge to feed into a questionnaire-style audit. This revised student- and research- led approach required participants to author their own skills list rather than choose from a pre-determined list of skills. This ensures that students are equipped to reflect on and develop their understanding of their skills independently.

| Before Workshop | After Workshop |

|---|---|

| Photoshop | Determination and commitment to tasks and activities |

| Documentation | Developing ideas/research |

| Resourceful | Visual and verbal communication skills |

| DIY | Research skills |

| Working with my hands | Stamina and willingness to put in long hours |

| Organisation | Management |

| Working independently | Organisation skills/documentation |

| Working in a team | Planning |

| Leading sessions | Photoshop, Premier and Illustrator |

| Managing a budget | |

| Writing Proposals | |

| Liaising with contacts | |

| Generating ideas | |

| Working in 2, 3 and 4 dimensions | |

| Time management |

Approaching a skills audit in this way encourages students to consider their skills in line with the changing needs of industry. The workshop discussions emphasised that the task of identifying one’s skills should not be an isolated one-off activity, but rather a continuous questioning and exploration of what new skills an individual has developed and how these relate to the ever-evolving needs of a particular industry.

The focus throughout the workshop was on creating unique lists of skills that effectively represented each individual and their subject area. Framing a skills audit in this context had the immediate effect of encouraging students to focus on their own skills audit and diminished any expectation that their list ‘should’ resemble that of anyone else. This is a key development, as the current skills audit questionnaire frequently led to unrealistic comparisons with those produced by others.

To further emphasise the value of creating a contained, personalised skills list, the pre- and post- workshop questionnaires encouraged students to engage in an ipsative model of self-assessment. An additional benefit of an ipsative model of self-assessment is that it enables students to become more self-reliant which ties in with the approach to independent learning that the workshop activities had focused on. The scope of this project did not allow for further investigation into how successful this element was, however, I am hopeful that there is real potential for further development of an ipsative model, which encourages participants to consider their own progress and improve self-awareness, rather than a comparison of their skills audit against that of their peers.

There are four key areas that need to be addressed when supporting students to identify their skills - confidence, the notion of expertise, skills articulation and embracing diverse skill sets.

When required to (such as in the case of the compulsory pre-workshop questionnaire) students can begin to create lists of their skills, but they find this task difficult. They are also generally unhappy with the results of their efforts. A move away from a pre-written skills audit questionnaire can result in students developing comprehensive and thoughtful, personalised skills lists, closely linked to their subjects and what employers are looking for. With the right guidance, students find it easy to complete a skills audit and are happier with the results. There is the potential to establish and expand upon an ipsative model for self-assessment in future iterations of this exercise. This would place value on the individual’s own progress rather than on external comparisons which are often unhelpful and irrelevant.

These conclusions open up a number of possibilities in terms of how I can support students to overcome challenges in future workshops. Encouraged by these findings and the positive feedback from students who participated in the research, my next steps will focus on designing an extended skills audit exercise. This revised exercise will position students as active participants who author their own skills lists, rather than passive learners mechanically working through a tick-box questionnaire.

There now also exists the opportunity to explore how students can map their skills against qualities, experience and behaviours using UAL’s recently launched ‘Creative Attributes Framework’ (UAL, 2016b). Understanding how a hands-on, student-focussed skills audit exercise might relate to the Creative Attributes Framework will further highlight to students how their course has enabled them to develop employability and enterprise attributes.

This more expansive, research-focused model will enable students to identify unique skill sets that are closely linked to their learning and the needs of the creative industries. This has the potential to open doors to work, freelance and collaborative opportunities for our students beyond their time at UAL.

“The workshop helped me to look at my skills in a new light and apply them to a design role. It was great to get more confidence from reading the skills section from prospects [website] and realising that many of the skills required to do a graphic design job, I have. I was just looking at my skills too narrow minded in an event management environment and couldn't see enough that the same set of skills can be applied elsewhere. The exercises also reminded me more of things/skills that I enjoyed using at university. Seeing how they were written down in your printed examples made them so much more accessible to talk about. Thank you!”

(Participant B, Breslin, 2016b)

Ball, L. (2008) ‘Bold resourcefulness:’ re-defining employability and entrepreneurial learning. London: University of the Arts London. Available at: http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/671/1/cltad_STAGE1OVERVIEWEXECSUM.pdf (Accessed: 21 November 2016).

Ball, L., Pollard, E. and Stanley, N. (2009) Creative graduates creative futures. Brighton: Creative Graduates Creative Futures Higher Education partnership and the Institute for Employment Studies. Available at: http://www.employment-studies.co.uk/system/files/resources/files/471.pdf (Accessed: 21 November 2016).

Breslin, H. (2016a) Pre-workshop questionnaire [email response]: Participant A, 8 March.

Breslin, H. (2016b) Pre-workshop questionnaire [email response]: Participant B, 11 March.

Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust (2016) Cognitive restructuring. London: NHS. Available at: http://www.cnwl.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/Cognitive_Restructuring_leaflet.pdf (Accessed: 21 November 2016).

Confederation of British Industry (CBI) and National Union of Students (NUS) (2011) Working towards your future: making the most of your time in higher education. London: CBI and NUS. Available at: http://www.nus.org.uk/Global/CBI_NUS_Employability report_May 2011.pdf (Accessed: 21 November 2016).

Hardy, B. and Ford L. R. (2014) ‘It’s not me, it’s you: miscomprehension in surveys’, Organizational Research Methods, 17(2), pp. 138-162. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1094428113520185.

Hughes, G., Okumoto, K., Wood, W. (2011) Implementing Ipsative Assessment. London: Available at: https://cdelondon.files.wordpress.com/2011/11/tra6finalreport_g_hughes.pdf

(Accessed: 24.11.16).

Kember, D. (2000) Action learning and action research: improving the quality of teaching and learning. London: Kogan Page.

McNiff, J. (2002) Action research for professional development: concise advice for new action researchers. 3rd edn. Dorset: September Books.

Nijjar, A. K. (2009) Stop and measure the roses: how university careers services measure their effectiveness and success. Manchester: Higher Education Careers Services Unit. Available at: http://www.hecsu.ac.uk/assets/assets/documents/Measure_the_roses.pdf

(Accessed: 21 November 2016).

Roth, C. L. (2015) Creative attributes framework. Internal report. Unpublished.

Sant, R. (2013) ‘The creative graduate’, International Entrepreneurship Educators Conference: Putting Students at the Centre of Enterprise, The University of Sheffield, 11-13 September. Available at: http://ieec.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/Richard-Sant-SOUTHAMPTON-SOLENT-UNI-IEEC_2013.pdf (Accessed: 21 November 2016).

University of the Arts London (2016a) About Careers and Employability. Available at: http://www.arts.ac.uk/student-jobs-and-careers/about-student-jobs-and-careers/ (Accessed: 21 November 2016).

University of the Arts London (2016b) Creative Attributes Framework. Available at: http://www.arts.ac.uk/about-ual/teaching-and-learning/careers-and-employability/creative-attributes-framework/ (Accessed: 21 November 2016).

Vagias, W. M. (2006) Likert-type scale response anchors. Clemson: Clemson University. Available at: https://www.clemson.edu/centers-institutes/tourism/documents/sample-scales.pdf (Accessed: 2 March 2016).

Hannah Breslin is an artist and educator, who works as a Student Employability Practitioner within Careers and Employability which is part of the Teaching and Learning Exchange at UAL. With a background in fine art and a creative practice spanning 10 years, Hannah undertook the PG Cert in Academic Practice in 2015/16 to explore the intersection between pedagogy and employability. Hannah combines her creative background and teaching interests to support students and graduates to discover their full potential beyond their time at UAL.

Understanding and Valuing your Skills

10 March 2016 (15:30 to 17:30), Room: A208, Chelsea College of Arts (UAL)

Workshop led by Hannah Breslin (2016)

Shared concerns or common themes that arose from the pre-workshop questionnaire and during workshop discussions (Hannah Breslin, 2016).

Analysis of language used by participants (identifying challenges)

| Confidence |

|---|

| ‘The confidence to reflect and identify personal strengths’ |

| ‘Unconfident in my strengths’ |

| ‘I feel like I'm not allowed to call myself a designer’ |

| ‘Not always confident enough in my work’ |

| ‘Non understanding of myself’ |

| Level of Expertise |

|---|

| ‘I tend to question myself and ask what are skills and whether or not I have enough, or even the right ones?’ |

| ‘Not enough expertise or experience in any to consider them as skills’ |

| ‘Sometimes I don't do something enough so I'm not sure I'm an expert’ |

| ‘Is that skill to a high enough standard that I can call it a skill?’ |

| Articulation and Definition of Skills |

|---|

| ‘Hard to accurately describe or name them’ |

| ‘Can't really identify them’ |

| ‘Just really thinking about if I can actually count some things as skill or not, maybe it’s a characteristic instead.’ |

| ‘Unsure of what can classify as a skill to share.’ |

| ‘Identifying what skills are’ |

| ‘Identifying personal skills not just software’ |

| Broad or Varied Skill Sets |

|---|

| ‘Too many interests and passions’ |

| ‘I have been participating in school societies but the skills are brief and broad’ |

| ‘I find myself confused about how to merge these two worlds I have experience in’ |