Dr Silke Lange, Associate Dean of Learning, Teaching and Enhancement, Central St Martins

Richard Reynolds, joint Head of Academic Support and Course Leader, MA Applied Imagination, Central St Martins

David White, Head of Digital Learning, Teaching and Learning Exchange

When art and design students and lecturers co-habit any kind of space, many relationships and interactions occur, only some of which are even loosely connected with learning and teaching. Do the activities which unfold in a studio or classroom define the space as a place for exploration, or do they imply a blocking of personal learning journeys? Specifically, if the psychogeography (Debord, 1955) of the learning space reproduces a hierarchical power relationship, can this be compatible with student-centred pedagogies and enquiry-based learning?

learning spaces, psychogeography, enquiry-based learning

Psychogeography is the study of specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behaviour of individuals. (Debord, 1955)

During a workshop held at the UAL Learning and Teaching Day at London College of Fashion (13 January 2016), we led a session where we used a number of techniques to disrupt the traditional format of a classroom or lecture space. Lectures and classrooms are often associated with static, immovable furniture organised in neat rows, all facing towards a whiteboard or screen, affording specific pedagogies, behaviours, rules and power structures. Our aim in the workshop was to challenge participants’ preconceptions of what might happen in such spaces. Using our observations and reflections on the workshop, this article explores how participants responded to and engaged with the different structures and activities imposed.

On arrival in the space, participants were asked to stand wherever they wished in the room, which had been temporarily stripped of its furniture. Arranged on the floor in a rough grid pattern were thirty-two envelopes. Each participant was invited to pick up the envelope nearest where they were standing, but not to open it until asked. We then continued with the discursive part of the session, during which it was possible to observe the participants moving around the room, in order to join and participate in the five separate loci of discussion. Not all, however, chose to move ‐ in some cases participants remained in the position or area which they had originally selected, participating only in the discussion group which was tied to the part of the room they had originally elected to stand in. During the discussion phase of the workshop, it also became apparent that the least active discussion was taking place at the rear of the space, opposite the door.

We were keen to actively involve participants in exploring questions around learning spaces and how we interact with them. To create an optimal discursive and inclusive environment, we used the widely-recognised Open Space Technology format (Owen, 1982) to initiate discussions amongst small groups of participants by posing questions such as: Is your studio or lecture-room a space or a non-space? Is it a home to learning, or simply a neutral zone for the transmission of information? What kind of learning journeys does this space facilitate? Does it have clearly-defined borders?

These questions were written on flipcharts, spread throughout the room, inviting participants to gather around them and start the discussion. We included an empty flipchart for participants who wanted to create their own question in relation to the theme. Here is a snapshot of the responses generated by participants:

‘self-discovery’, ‘reflection’, ‘collaboration’, ‘connections’, ‘conflict’, ‘collusion’, ‘communication’, ‘confidence’, ‘individual journey’, ‘group processes’, ‘asynchronous’, ‘amplification’, ‘practice-based’, ‘open conversation’, ‘research journey’, ‘frames particular disciplinary ways of knowing’ and ‘enable alternative routes’.

‘We don’t have a space: we’re parasites, we don’t always teach in a room: we prefer visits.’

‘I only do one type of activity in a studio, many more elsewhere, multiple activities in one space.’

‘Flexible borders within the space.’

‘Who is the border between? Define ‘border’ ‐ pejorative?’

‘I’m into amoebas: stretchy borders, conflicts within shared space, acoustics of open studio spaces ‐ how do students learn in a wall of noise?’

‘Privacy, intimacy? Most private in the open.’

‘Hitchcock, hiding in the dark...’

‘Sound affects learning, silence, conditions of learning, individual and collective.’

‘Appropriation of space ‐ ownership of space, feeling safe even if only temporary [...].’

‘What about conceptual space?’

‘What if you have no agency over the spaces you teach in?’

‘What if you have no fixed studio space? The aqueduct of the university? (Extending non-space and extending the ‘borders’ question)’

‘Can ‘digital space’ in a studio disrupt a constructed group dynamic/studio space?’

The participants’ own questions address the purpose of twenty-first century learning spaces in creative arts education, which encourage students to take ownership of their ‐ predominantly ‐ self-directed learning; collaborate with their peers as well as tutors, and adapt to a range of working environments.

The notion of active learning spaces has been discussed widely in educational literature by Jos Boys (2011), Phillip Race (2001), Aileen Strickland (2014) and Paul Temple (2007), amongst others (see reference list below). The responses of the educators who participated in the workshop demonstrate that they are either implicitly or explicitly aware of these debates about active learning spaces and their attendant psychogeography. In particular, the responses to the question about learning journeys reveal a widespread desire to create an open-ended learning environment, as the use of words and phrases such as ‘self-discovery’, ‘collaboration’, ‘connections’, ‘open conversation’, ‘research journey’ and ‘alternative routes’ clearly evidence. But to what extent are educators able to understand how their learning spaces are experienced from the perspective of the student? The experiment with the envelopes had been designed to demonstrate just how deeply programmed we are to respond to the power structures of a learning space in predictable ways.

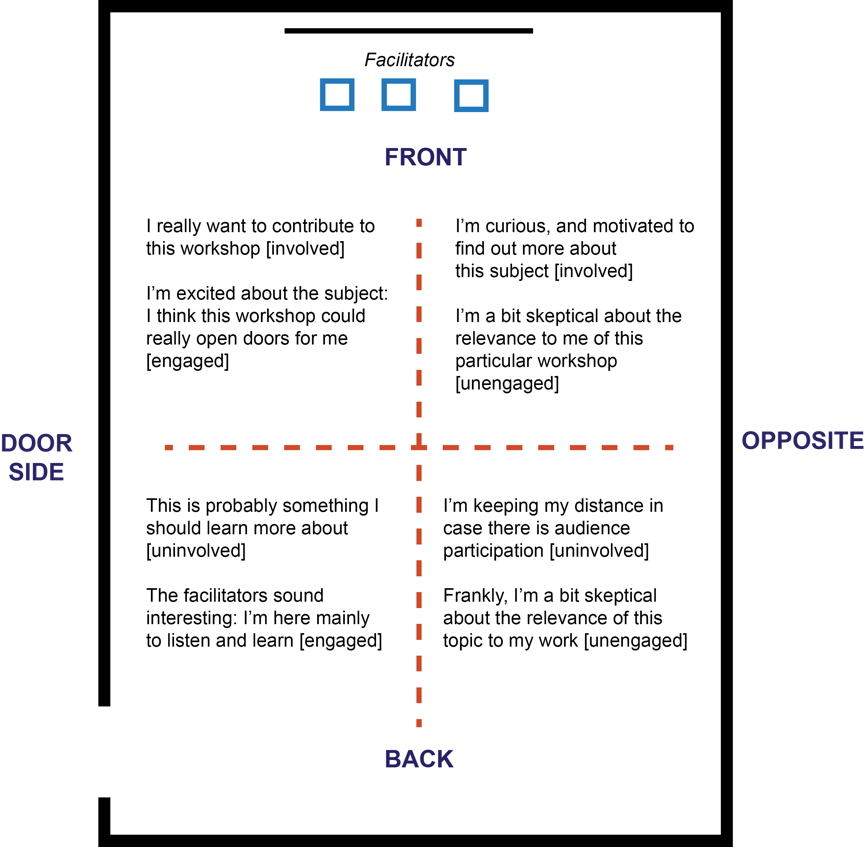

Once the facilitated discussions were concluded, participants were invited to open their envelopes. Interestingly, one participant in the workshop ‐ who had placed themselves at the front and opposite the door ‐ had already jumped the gun and opened theirs. The envelopes contained a card, on which was printed one of four different texts. The nature of the text depended on which quadrant of the room the participant had chosen to stand in: front near door; front opposite door; rear near door; and rear opposite door. The wording of the various texts was based on the theoretical model that those who position themselves near the front of a learning space (close to the perceived seat of power) are the most involved in its discourse, and those who position themselves on the side near the door are the most engaged in the perceived ideology of the learning activity. Crossing the lecturer’s position of power at the front, in this reading of teaching spaces, is a direct challenge to the lecturer’s authority (Reynolds, 2016).

Once the envelopes had been opened, three random participants from each part of the room were chosen to read the text on their card out loud, and to state whether the attitudes towards the session expressed were similar to their own on arrival at the workshop. In practice, only two volunteers were forthcoming from the rear of the room opposite the door, a space which had gradually emptied as the session had unfolded.

All except two of those who were asked to read out their text expressed broad and, in most cases, profound agreement with the attitudes predicted on their card, including both sections of the predictive text. The only two dissenting voices came from those who had initially been standing at the front of the room, opposite the door. This is the area of any learning or workshop space where our theoretical model predicts both methodological challenge and intellectual dissent, and this is precisely what occurred (Reynolds, 2016). Specifically, those at the front opposite the door all accepted part one of the prediction (‘I’m curious, and motivated to find out more about this subject’), but disputed in two cases the suggestion that they were ‘sceptical about the relevance to me of this particular workshop’. If this workshop is repeated in the same format, it might be instructive to change the wording of part two of the prediction text for the front/opposite space to refer to something more intellectually provocative than ‘relevance’. It might be more revealing to suggest that those who position themselves at the front and opposite the door have reservations about the theoretical and methodological basis of the workshop itself. This would invite such participants to voice their criticisms of the workshop’s methodology in the face of their conformity with the model’s prediction that their positioning of themselves within that part of the room makes it predictable that they would do this.

The high percentage of successful predictions by the texts on the cards produced a powerful reaction among the participants. There were no dissenting voices from those who had not been asked to read out the text on their cards. The room as a whole was broadly convinced of the validity of the predictive psychogeographic model.

As the facilitators of the session, we were careful to position ourselves at the front of the room as the participants entered. The front was visually demarcated in the normal manner by traditional cues such as the screen for the digital projector, the presentation lectern and computer. As is usually the case, the door to the room was at the opposite end to the front.

However, we suggest that the location of the facilitators was the substantive element in defining the ‘front’ of the room and its concomitant psychogeography. Even though the session was designed to be extremely open and discursive in manner, participants clearly responded to the facilitators as being ‘in charge’ of the session and located themselves relative to this. In essence, the psychogeography of the room was formulated around implicit responses to power and the traditionally accepted hierarchy of expert/teacher and student/participant. This appeared to be the case even though all the participants in the session were colleagues, some of whom were senior to the facilitators within the employment structure of the university.

This phenomenon was also evident during the post group-work discussion, which took place while everyone was standing. Despite employing as gentle a form of ‘chairing’ as possible, participants gradually formed a semicircle around the facilitator who was guiding the discussion. This formed a new ‘front’ of the room which, in this case, was at 90 degrees to the normal layout (had the chairs been in use). This psychological layout remained in place even when participants who formed part of the semicircle were reflecting at length about the group activity.

One of the implications of this workshop is that there is a degree of denial among lecturers concerning their relationships with the spaces where learning takes place. To put it simply, there was a certain dissonance between the participants’ view of themselves as facilitators of open and unstructured learning, and the predictable and structured way in which these same individuals responded to a power-inflected space, when they themselves were placed in the -geographical position of students. Our workshop demonstrated how difficult it is to remove the power element from any learning space, however much the lecturer or facilitator may feel that they are working from a ‘flexible’, ‘shared’, ‘open’ or ‘stretchy’ agenda.

We live in a society shaped by the application of power, and one way in which power is expressed is through the psychogeography of the spaces in which it operates. Deeply ingrained expectations and responses to the power of psychogeography cannot be instantaneously switched off, however desirable this might be. Even where apparently ‘levelling’ pedagogies are employed, tacit responses to assumed power continue to have a significant effect on how a learning space is used and configured. This points to a need to actively disrupt the psychogeography of the teaching space if equitable discourse or co-production of knowledge are desired. Ruth Dineen’s research into the development of creativity in art and design highlighted a contrary view on relationships in the teaching space:

The non-hierarchical nature of the relationship was frequently reiterated: ‘it’s about an attitude between staff and students...my job is not to impose how I see the world’. (2006, p.112)

If it is common practice in art and design subjects to create a non-hierarchical relationship between students and staff, why are we still looking for the educator who supposedly holds all the knowledge and stands at the front of the room? Is this really justified, with so much information being freely available in the virtual environment? In a blended learning space, containing physical and digital interactions and discourses, where is the seat of power actually located? There is an urgent need to configure a new psychogeography of teaching and learning spaces, which will be responsive to the advent of blended learning, as well as reflecting our frequently-stated desire as educators to democratize the learning process.

Benedict, M.E. and Hoag, J. (2004) ‘Seating location in large lectures: are seating preferences or location related to course performance?’, The Journal of Economic Education, 35(3), pp. 215-231.

Boys, J. (2011) Towards creative learning spaces: rethinking the architecture of post-compulsory education. London: Routledge.

Debord, G. (1955) ‘Introduction to a critique of urban geography’, in Knabb, K. (ed.) (1981) Situationist International Anthology. Oakland: Bureau of Public Secrets.

Dineen, R. (2006) ‘Views from the chalk face: lecturers’ and students’ perspectives on the development of creativity in art and design’ in Jackson, N., Oliver, M., Shaw, M. and Wisdom, J. (eds.) Developing creativity in higher education: an imaginative curriculum. London: Routledge. pp. 109-117.

Gossard, M., Jessup, E. & Casavant, K. (2006) ‘Anatomy of a classroom: An exploratory analysis of elements influencing academic performance’, North American Colleges and Teachers of Agriculture Journal, 50(2), pp. 36-39.

Holliman, W.B. and Anderson, H.N. (1986) ‘Proximity and student density as ecological variables in a college classroom’, Teaching of Psychology, 13(4), pp. 200-203, http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15328023top1304_7.

Horne Martin, S. (2004) ‘Environment behaviour studies in the classroom’, Journal of Design and Technology Education, 9(2), pp. 77-89.

Kalinowski, S. and Taper, M.L. (2007) ‘The effect of seat location on exam grades and student perceptions in an introductory biology class’, Journal of College Science Teaching, 36(4), pp. 54-57.

Lave, J. and Wenger, E. (1991) Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

MacPhee, L. (2009) ‘Learning spaces: a tutorial’, Educause Quarterly Magazine, 32(1). Available at: http://er.educause.edu/articles/2009/3/learning-spaces-a-tutorial (Accessed 8 June 2016).

Mehan, H. (1979) Learning lessons: social organization of the classroom. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Owen, H. (2008) Open Space Technology: a user’s guide. 3rd edn. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Pedersen, D.M. (1994) ‘Privacy preferences and classroom seat selection’, Social Behaviour and Personality: an international journal, 22(4), pp. 393-398.

Race, P. (2001) The lecturer’s toolkit. 2nd edn. London: Kogan Page.

Reynolds, R. (forthcoming 2016) ‘Psychogeography and its relevance to inclusive teaching and learning development: why it matters where students choose to sit’, Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education, 10.

Seifert, K. & Sutton, R. (2007) Contemporary educational psychology. Wikibooks. Available at: http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Contemporary_Educational_Psychology (Accessed: 7 June 2016).

Stehle, M. (2008) ‘Psychogeography as teaching tool: troubled travels through an experimental first-year seminar’, InterActions: UCLA Journal of Education and Information Studies, 4(2). Available at: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/3xv3634r (Accessed 8 July 2016)

Strickland, A. (2014) ‘The active agency of learning spaces’, in Scott-Webber, L., Branch, J., Bartholomew, P. and Nygaard, C. (eds.) Learning Space Design in Higher Education. Oxfordshire: LIBRI Publishing, pp. 209-224.

Temple, P. (2007) Learning spaces for the 21st century: a review of the literature. London: Centre for Higher Education Studies, Institute of Education, University of London. Available at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/sites/default/files/learning_spaces_v3.pdf (Accessed: 8 June 2016).

Totusek, P.F. and Staton-Spicer, A.Q. (1982) ‘Classroom seating preference as a function of student personality’, Journal of Experimental Education, 50(3), pp. 159-163, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00220973.1982.11011818.

Wulf, K.M. (1977) ‘Relationship of assigned classroom seating area to achievement variables’, Educational Research Quarterly, 2(2), pp. 56-62.

Dr Silke Lange is Associate Dean of Learning, Teaching and Enhancement at Central Saint Martins. Silke’s research encompasses the creative process, collaborative learning, interdisciplinarity, learning environments and the student as co-creator. She has been involved in projects such as the ‘Innovators Grant 2015’ at the Node Centre in Berlin and Broad Vision, an interdisciplinary art / science research and learning programme. Her recent investigations into learning environments have been published in an international anthology on Learning Space Design as a co-authored chapter entitled: Promoting Collaborative and Interdisciplinary Learning via Migration between different Learning Spaces.

Richard Reynolds completed his Masters in Anglo-American Studies at Oxford University in 1982. From 1983 to 2010 he worked in the publishing industry, and served as Managing Director of Reynolds & Hearn Ltd from 1999 to 2010. Richard has taught at Central Saint Martins since 1994, and has been Joint Head of Academic Support at CSM since 2013. He is also Course Leader for MA Applied Imagination in the Creative Industries. His best-known published work is Superheroes: A Modern Mythology (Batsford 1992, Mississippi 1994).

David White is Head of Digital Learning in the Teaching and Learning Exchange at UAL. He researches online learning practices in both informal and formal contexts. David has led and been an expert consultant on numerous studies around the use of technology for learning in the UK higher education sector and is the originator of the ‘Visitors and Residents’ paradigm, which describes how individuals engage with the Web.