Jacqueline Winston-Silk, Curator, Archives & Special Collections Centre, London College of Communication

The Reimagining project provides a new way of thinking about the collections held by each of the colleges of University of the Arts London. In developing this approach to object-based learning, students from the MA Designer Maker programme at Camberwell College of Arts (UAL) were invited to work with a pool of deaccessioned material from the ‘Camberwell ILEA Collection’. Students were briefed to boldly reimagine some of the objects. The resulting work, featured in the exhibition A Narrative of Progress: The Camberwell ILEA Collection (Camberwell Space, October–September 2018), provides a provocation on the meaning of making and the value of such material within higher education.

special collections; object-based learning; deaccessioning; reimagining; making

The Camberwell ILEA Collection contains iconic design, craft and studio pottery by prominent makers of the Modern period. First assembled in 1951, the collection was conceived by the Council of Industrial Design (COID) and the London County Council, and latterly managed by the Inner London Education Authority (ILEA). The original purpose of the collection was to teach children the principles of ‘good design’ through the study of objects and materials. This ambitious project was known as the Experiment in Design Appreciation and later renamed the Circulating Design Scheme. COID, and later ILEA, amassed an extensive handling collection and formalised a lending programme. Objects were mounted in purpose-built showcases which opened to reveal ready-made displays for the classroom. These ingenious cases were circulated to London secondary schools; children were permitted to handle the contents and teaching staff were free to incorporate the displays into their curriculum. Displays encouraged curiosity and were responsive to the cultural landscape. Emerging ideas, such as the impact of pop-art, the craftsman in the machine age and the influence of Japanese culture, all featured. The Circulating Design Scheme was ambitious, forward-thinking and widely adopted within London schools during the 1960s. After the closure of the Scheme and ILEA’s eventual disbandment, the objects were donated to Camberwell College of Arts.

ILEA’s approach to learning though objects was shaped by staff, including Art Officers and Museum Educators, which chimes with UAL’s commitment to object-based learning where archives and special collections are embedded into academic practice at all levels. Object-based learning, as a pedagogic practice in art and design higher education, was explored and defined by Dr Helen Chatterjee and Dr Leonie Hannan. By integrating museum collections in tertiary-level learning, objects have a role in the “acquisition and dissemination of subject-specific and cross-disciplinary knowledge, observational, practical and other transferable skills” (Chatterjee, Hannan and Thomson, 2015, p.1).

In previous issues Spark has reported on the role of object-based learning within transformational education. An article from Graham Barton and Judy Willcocks (2017) describes their development of workshops in which object-centred activities encouraged student self-enquiry. Entitled ‘Object-based self-enquiry: a multi- and trans- disciplinary pedagogy for transformational learning’, it reflected on the coming together of museological teaching practice and learning development.

In a recent collections review (2018), the Archives & Special Collections Community of Practice audited UAL’s holdings, concluding that across all six colleges UAL holds more than 140 individual collections. Collections-focused staff working within the University’s libraries, archives, museum and special collections continue to seek opportunities to enhance teaching and learning, along with the student experience, by way of exposure to UAL’s abundance of material culture.

There are many ways in which objects can be used within academic practice. Object literacy or reading objects encourages interrogation skills, the formation of original ideas, and acts as a compelling basis for original research. Haptic learning (or learning through the use of touch) includes handling objects. It allows informed conclusions to be made about materials and processes of making, but moreover it offers “a deeper and more memorable learning experience” (Willcocks, 2018, p.46). Similarly, ‘slow looking’ is an approach used within museum and gallery education whereby “close, prolonged looking results in a deeper understanding and a more meaningful experience” between the visitor and the exhibit (Ferreia, 2015). Slow looking can be adopted within higher education (Tishman, 2018) to illustrate a student’s inherent way of questioning and thinking, and to draw out multiple meanings. This approach is used successfully with the University’s Researching Skilfully workshops, co-delivered by staff from Academic Support and the Archives & Special Collections Centre.

Objects can act as powerful metaphors enabling abstract ideas to be communicated and understood. In the context of the digital world, objects can be seen to illustrate a form of ‘truth’; an object’s extant materiality acting as evidence in lieu of surviving texts. Objects can illuminate wider social-historical discussions or illustrate movements in art and design. On a more practical level, objects can provide inspiration for creative briefs, be used in the teaching of new digital technologies and play a crucial role within the development of a student’s curatorial practice.

Over the last three years efforts have concentrated on the development of the historic Camberwell ILEA Collection. This has involved two intense periods of cataloguing and digitisation work, overseen by the appointment of a dedicated curator. These initiatives have succeeded in increasing the discoverability of the collection and in meeting accepted standards of care. These activities aim to establish the Camberwell ILEA Collection as a rich (and accessible) resource in creative artistic practice while encouraging critical engagement with the materials in the collection. Secondly, these activities strive to recognise the significance of the collection and to position it within the wider discourses of design pedagogy, object-based learning and histories of collecting. Estimated today to be in excess of 5,000 objects, half of the collection is now available to search online for the first time – a significant milestone (UAL, 2019).

Archives and special collections have restrictions surrounding the use of materials for good reason. Collection managers and archivists strive to ensure the integrity and preservation of their collections for future use. Safe handling, exposure to light, inert material housings and the removal of ink pens are just a few of the practices employed in the custodianship of historic, valuable or significant materials. Indeed, use of such material is often constrained by its very inclusion within a permanent collection, and the (perceived) status bestowed upon it.

Through the process of deaccessioning (a collections management procedure whereby accessioned items are removed from a permanent collection) a small group of objects were made available for use. Items were deaccessioned due to their poor physical condition. For example, damaged objects or incomplete parts were removed from the main collection, as were items contaminated by mould or excessive rust. In short, deaccessioning ensures a collection remains manageable. Rather than disposing of these spoiled materials, they were offered to MA Designer Maker students with no restrictions upon how the objects were to be used. The course programme encourages students to engage in debates around applied arts, design and object-based art. As well as exploring materials and processes, the meaning of making and human-object relationships. As a collaboration between students on the course and the curator of the collection, the Reimagining project offered a rare opportunity for students to work with and manipulate historic objects, where the materiality of each object became a medium to explore.

The pool of disposed objects included Scandinavian homeware by Skjode Skjern, where the teak wood was rippled with tide marks. Collectable domestic plastics by Melaware were sandwiched in-between inappropriate packing materials. Japanese cast-iron cookware by Tokaido housed dense blooms of fluorescent corrosion. Glazed ceramic fragments, hand-made by Cornish potter Wilfred Gibson, once belonged to now disembodied figurines.

The deaccessioned objects - imbued with the biographies of their makers, made richer by their association to ILEA’s Circulating Design Scheme - resonated strongly with this group of contemporary makers. The ‘unwanted’ objects provoked debates over value, patina, repair, design and the act and meaning of appropriation. These ideas converged in the process of reimagining. Encouraging the students to think through making, as a form of object-based learning, the project culminated in 8 original works, which incorporate disciplines including ceramics, metalwork, sculpture, woodwork, fine art and model building.

The MA cohort first encountered the objects during a taught studio session. The history and provenance of the collection was shared with group, supported by access to original archive material. Students were introduced to the notion of de-accessioning within the context of curatorial practice. Students were able to handle objects throughout the project, with two boxes of material taking up permanent residence in the studio space, giving sustained access. The project was co-delivered by Maiko Tsutsumi, Pathway Leader, and benefitted considerably from insight by maker, Bridget Harvey. The brief to reimagine one object of your choosing was deliberately left open, in order to accommodate a range of making practices.

Within the written brief students were given a series of key words which included: complete, repair, transform, change the function, de-contextualise, re-contextualise, narrative, agency, conservation and salvage. The written brief also prompted students to:

Students were asked to submit a proposal for their reimagining, and were encourage to produce prototypes and/or provide visual ideas. Proposals were shared in a small group seminar in which peer feedback was given. Participants were given 6 weeks to complete final reimagined work.

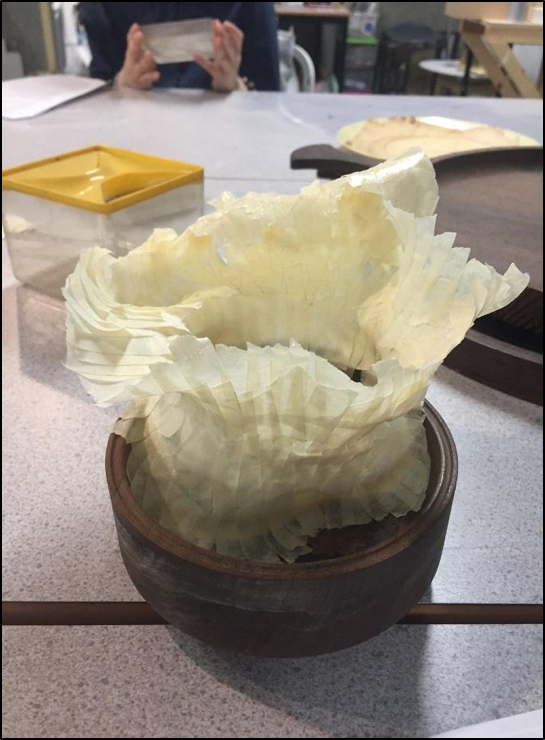

One student from the MA Designer Maker programme reimagined a hand-turned bowl, made by British woodworker George Sneed in around 1965. The bowl was deaccessioned from The Camberwell ILEA Collection because of damage caused by water ingress. The student created a sculptural adornment using pieces of masking tape. These adornments were inspired by the historic labels often found on objects in the permanent Camberwell ILEA Collection.

One student from the MA Designer Maker programme reimagined a pewter saucer, designed by Gerald Benney, CBE and manufactured by Viners of Sheffield (c.1951). The saucer was deaccessioned from The Camberwell ILEA Collection because the metal was misshapen and damaged. The student created a set of porcelain accoutrements, each carefully misshapen. The work has been shortlisted for The Batsford Prize 2019, in the applied arts category.

The eight works produced by the students were given prominent feature in the exhibition A Narrative of Progress: The Camberwell ILEA Collection at Camberwell Space, the college’s free public gallery from 18 September to 27 October 2018. This exhibition reflected on the origins of the collection, presented recent collections management activity and showcased how the collection can be used as a resource in teaching and learning. Students were invited to install their work in the gallery and to create a short piece of writing to describe their process. The Reimagining project demonstrated the relevance of the collection to contemporary arts practice at the University.

At the close of the project and exhibition, both makers and collection managers questioned the status and ownership of the hybrid works. There was no current precedent at UAL. For Harvey, the act of (re)making allows an object to be, ‘salvaged in dynamic and sometimes irreversible ways […] having been twice made’ (2015). She argues the act of reimagining allowed her to colour outside the lines of the original, without obscuring what was there before. The works felt neither wholly the property of the collection, nor the makers.

As such, and in celebration of the maker’s interventions, participants were invited to donate their reimagined work, to form the basis of a new collection. A body of work which compliments and provides a counterpoint to the parent collection, and one which encourages provocations surrounding the meanings of making.

Due to the fact that the deaccession of artefacts in collections tends to be infrequent, the Reimagining project cannot be easily replicated. Nevertheless, this collaborative object-centred project offers an alternative way of thinking about collections and proposes a model for creatively working with de-accessioned material. The approach of reimagining and re-activating objects earmarked for disposal outlined in this article, could be adopted by other archives and special collections - especially those which face similar concerns about storing damaged material. Using object-based learning, the Reimagining project invites the reappraisal of such material and questions its value within current educational contexts.

Barton, G. and Willcocks, J. (2017) ‘Object-based self-enquiry: a multi- and trans- disciplinary pedagogy for transformational learning’, Spark: UAL Creative Teaching and Learning Journal, 2(3). Available at: https://sparkjournal.arts.ac.uk/index.php/spark/article/view/75/129 (Accessed: 20 February 2019).

Chatterjee, H.J. and Hannah, L. and Thomson, L. (2015) ‘An Introduction to Object-Based Learning and Multisensory Engagement’ in Chatterjee, H.J. and Hannah, L. (2015) Engaging the Senses: Object-based Learning in Higher Education. London: Routledge, pp.1–20.

Ferreira, K. (2015) ‘320 Hours: Slow Looking and Visitor Engagement with El Greco”. Available at: https://artmuseumteaching.com/2015/07/31/320-hours-slow-looking-visitor-engagement-with-el-greco/ (Accessed: 26 April 2019)

Harvey, B. (2018) ‘Reimagining the collection: a large box of loose parts’, A Narrative of Progress: The Camberwell ILEA Collection. Exhibition curated by Jacqueline Winston-Silk, held Camberwell Space, Camberwell College of Arts (University of the arts London), 18 September to 27 October 2018. Available at: http://bridgetharvey.blogspot.com/2018/09/reimagining-collection-large-box-of.html (Accessed: 20 February 2019).

Tishman, S. (2017) Slow looking: The art and practice of learning through observation, Routledge 2017.

University of the Arts London, UAL (2019) The Camberwell Inner London Education Authority (ILEA) Collection. Available at: http://collections.arts.ac.uk/collections/camberwell_ilea (Accessed: 20 February 2019).

Willcocks, J. (2018) ‘Object-based learning and the modern art school curriculum’, Ed. Kullberg, M. (2018) Visual Arkivering 14 The Art Academy Collections. Learning from Objects. Published in connection with the international symposium ‘Learning from Objects’, 21 June 2018.

Jacqueline Winston-Silk is a Curator based at UAL’s Archives & Special Collections Centre at London College of Communication. She is responsible for object collections including the historic Camberwell ILEA Collection and the David Usborne Collection. Jacqueline held previous roles at the University of Reading's Museums and Special Collections Service, the Museum of Domestic Design & Architecture at Middlesex University, the Geffrye Museum, the Design Museum and Tate.