Robin Sampson, formerly Assistant Archivist, University of the Arts London Archives and Special Collections Centre

For students a tour of the University of the Arts London Archives and Special Collections Centre (ASCC) can be a passive learning experience; they receive a large amount of information with limited opportunities to engage with archive material. ‘Escape Room Games’ (ERGs) offer a more active and engaged learning experience. They suit a constructivist learning agenda and also act as an experiential, immersive way to be introduced to archival holdings. ERGs are co-operative, participatory games in an immersive fictional setting, where teams of players collaborate to solve linked puzzles and accomplish goals. These games are ideally suited to educational environments, as they co-opt key learning methodologies into a time-limited, rewards-based session. This article showcases an example of an escape room game created and utilised at the University of the Arts London’s ASCC.

gamification; co-operative learning; participatory learning; immersive learning; constructivism

The Archive and Special Collections Centre (ASCC), based at the London College of Communication (LCC), is one of several special collection centres operated by the University of the Arts London (UAL). The ASCC is the repository for around thirty archives and special collections with a particular focus on film-making, graphic design and printing, sound arts, comic books and photography, and also holds the institutional archives of UAL and LCC. It is particularly notable for holding the archive of the film-maker and auteur Stanley Kubrick. A significant part of the ASCC’s remit is to provide internal access to these collections in order to enhance and enrich the learning experiences and research opportunities for staff and students at UAL.

The ASCC provides a number of induction offers for UAL course cohorts, in order to provide them with an introduction to the archives and collections and how they could be accessed and utilised. These offers include: ‘highlights’ tours of items from selected collections, on-site workshops that teach research and analytical skills (‘Researching Skilfully’, ‘Researching with Archives’) and off-site sessions that take the collections out to classrooms across the University (object-based learning sessions, world cafe knowledge-sharing events). The commonality between these offers is that they are educator-led: when on-site the tours and workshops are predominantly presented by members of the archive staff. When off-site the staff assist the tutor with the workshop or invigilate the handling of the collections. This approach has the positive effect of showcasing the collections to a sizable audience, and offers can be tailored to particular courses or research interests. The archive staff’s enthusiasm and knowledge of the subjects can be transferred directly to the audience, and spark the desire for an individual to return to the ASCC to make use of the collections for private research.

However, there are aspects of a comprehensive learning experience that are not covered by these offers. For students, a tour of the ASCC can be a passive experience; they receive a large amount of information with limited opportunities to engage with the material, and many feel intimidated when presented with the chance to ask questions in front of their peers. Workshops and classes offer a greater opportunity for students to engage with the material, but this is still within the context of a learning environment where the parameters of the class have been formulated in advance by the educator.

‘Escape Room Games’ (ERGs) offer an alternative learning experience. They suit a constructivist learning agenda and also act as an experiential, immersive way to be introduced to the ASCC holdings. They are predominantly interactive, and students have a greater agency over how they participate in the session. The educator sets out the game scenario, parameters and expected goal (usually ‘escaping’ the room), and from then becomes an aspect of the gameplay; their role is not to actively guide the session, but rather to provide assistance only when requested. Players instead work together from the offset, immediately establishing roles and workflows within the team and testing their problem-solving capabilities. The immersive nature of the session reduces the risk of participants feeling self-conscious, and they interact with each other rather than a perceived authority figure.

ERGs are defined as immersive, live-action, co-operative team-based games where players discover clues, solve puzzles and accomplish tasks in a ‘locked’ room. These tasks are completed in order to accomplish a specific goal – usually ‘escaping’ from the room – in a limited timeframe (Nicholson, 2014). ERGs have a number of important attributes, which together provide opportunities for active engagement, and follow the constructivist approach to learning, emphasising collaboration between students over passive reception of information (Burns and Shumack, 2017).

ERGs are a natural extension of the classroom and the types of learning environments and activities that students are already familiar with (Nicholson, 2018). They are ‘collaborative, problem-based, time-constrained and active’, all of which are elements that educators desire in optimum learning outcomes (Monaghan and Nicholson, p.49). An educational setting suits ERGs because they are ‘co-operative challenges that take place in the physical world, which gets players out from behind their screens and working with each other directly’ (Nicholson, p.44).

ERGs provide multiple opportunities to test students’ analytical skills. Students rely on their abilities to make connections between items, to test hypotheses (for example, whether a perceived relationship between two game pieces will result in the desired outcome of solving a puzzle), and to eliminate the results of unsuccessful deductions. Further to this, an ERG’s inbuilt time limit creates a sense of urgency that focuses the students’ engagement with the game, allowing for more reflective discourse after the game’s completion (Nicholson, 2018).

The use of ERGs in an educational setting also presents the opportunity for students to be creators as well as participants. ERGs comprise several elements: genre, setting, world, narrative and challenges (Nicholson, 2016). These elements are key in providing opportunities for creativity in a Higher Education environment. One of the catalysts for the author to develop an onsite, archive-based escape room game was LCC’s MA Games Design programme, which includes a module on ERG design. A subsequent course module required students to collaborate with an external agent in the design of a game. The author therefore proposed a collaboration with a course student, as this was the ideal opportunity to develop an archives-based game both as a creative exercise and to trial a constructivist educational offering.

The author made contact with Dr David King, course leader on LCC’s MA Games Design course, to initiate a collaboration. A call-out was made to students on the programme and one of them, Andy Li, volunteered to participate in the game design process. The decision was taken to focus on the Stanley Kubrick Archive for thematic and game mechanism inspiration. The Stanley Kubrick Archive provided a strong basis due to the familiarity of Kubrick’s films within popular culture and also because of the richness and variety of material in its holdings. Andy was creatively responsible for designing the mechanics of the game. The author worked with Andy to source archive items that could be used as a basis for puzzle designs, the game’s scenario and narrative.

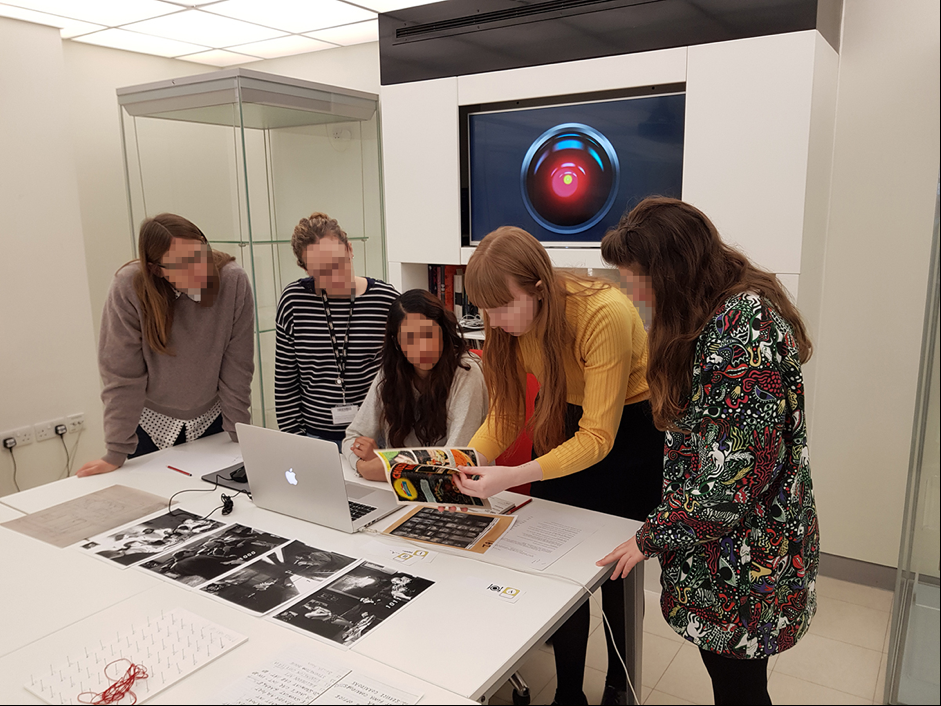

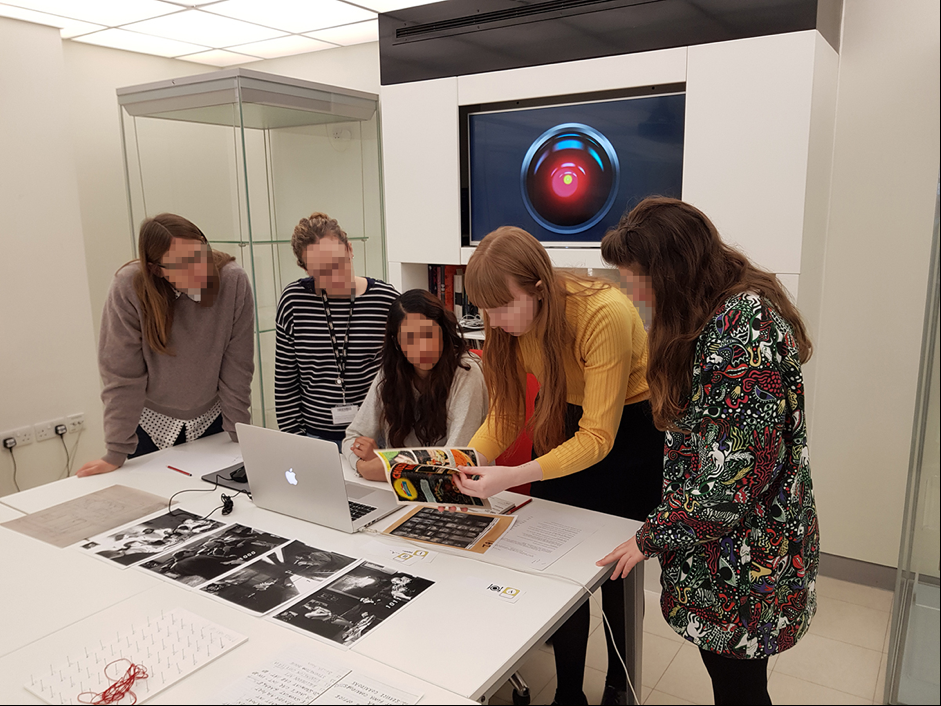

It was decided that thematically the game would be loosely based on the Kubrick film 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). LCC had recently held an exhibition of student work inspired by this film, and the ASCC itself had been architecturally inspired by one of its iconic sets, which would significantly enhance the thematic elements of the game. Development and testing was undertaken during January and February 2018. Upon completion the session was unveiled as part of UAL’s 2018 Research Fortnight and has subsequently been utilised for sessions with staff, students and offer-holders as an introduction to the archive holdings.

At the time of writing eight teams of participants have taken part in ERG sessions run at the ASCC or as part of external events. Feedback has been gathered informally through interviews with participants immediately after sessions and subsequently via email. A more formal collation of data could be achieved through feedback surveys such as the example presented in the Appendix. The feedback has anecdotally been generally positive, with participants expressing enthusiasm for the excitement generated by the tension of the timed game and the feeling of satisfaction and progress engendered by successfully completing a puzzle. It has been observed that there is generally a high level of interaction between team members, who assign roles and take systematic approaches to solving puzzles. The variety of puzzle styles within the game meant that team members can each contribute and have a chance to ‘be the hero’ due to their own specialist knowledge and skill sets.

Participants also stated that the game has made them more aware of the archive space and the holdings of the Stanley Kubrick Archive, and has given them the desire to revisit and explore the collection in more detail. This has been corroborated by participants in similar archive-based games (Lawrence, 2018).

Some participants who were less familiar with the concept of escape rooms initially struggled with the concept, and in some cases this initial confusion reduced the level of excitement and engagement. However, as games progressed players often noted that they became more used to the processes and game mechanics. Even those who did not successfully complete the game more often than not expressed a level of enjoyment and positive engagement with the archive material.

A limiting factor was that the logistics of the game mean that there is a restriction on attendee numbers in comparison to archive tours (where there is space for up to 15 attendees) or workshops. Playtesting showed that 3-5 participants is the optimum number of team members; more than 5 resulted in some players being side-lined with reduced opportunity to participate, whilst smaller teams struggled to complete the game within the designated time limit.

The limitation on participation numbers has been partially negated by the development of a portable version of the game that allows two or more teams to attempt the ERG simultaneously in a larger setting, introducing a competitive element between teams. There is also the opportunity to further develop the concept to create a fuller learning experience, with a more extensive set of puzzles that could be tailored to reflect the pedagogical needs of different courses in the same way as the tours and workshops offered by the ASCC.

It would also be useful to obtain formal evaluations of the game by the collection of participant data via feedback forms (see the Appendix for an example). This would allow the identification of gameplay issues and to identify target demographics.

ERGs are participatory, co-operative, immersive and promote active learning, all elements that are encouraged in a constructivist approach to education. The game developed for use at the ASCC showcases the utilisation of archive and collection material as a stimulus for creative game development within an arts-based learning environment. It also presents an entertaining and memorable learning activity, in which participants can gain an entry-level understanding and appreciation of the holdings in a more active manner than other outreach activities currently offer. Players are put at the centre of the learning experience (Nicholson, 2018). Archives and special collections centres are increasingly turning to ERGs to showcase their collections and provide participatory user experiences (US National Archives, 2018) and the arts-based nature of UAL’s collections and programmes have provided a perfect opportunity to further develop this concept.

Burns, L.S. and Shumack, K. (2017) ‘On-campus or online: Learning resources and communities of practice make the difference’, Spark: UAL Creative Teaching and Learning Journal 2(2), pp.111–122. Available at: https://sparkjournal.arts.ac.uk/index.php/spark/article/view/47/80 (Accessed: 5 April 2019)

Monaghan, S. and Nicholson, S. (2017) ‘Bringing escape room concepts to pathophysiology case studies’, HAPS Educator, 21(2), pp.49–65. http://dx.doi.org/10.21692/haps.2017.015.

Nicholson, S. (2018) ‘Creating engaging escape rooms for the classroom’, Childhood Education, 94(1), pp.44–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2018.1420363.

Nicholson, S. (2016) ‘Ask why: creating a better player experience through environmental storytelling and consistency in escape room design’, Meaningful Play Conference 2016, Lansing, Michigan, 20–22 October. Available at: http://scottnicholson.com/pubs/askwhy.pdf (Accessed: 21 February 2019).

Nicholson, S. (2014) ‘A RECIPE for meaningful gamification’ in Wood, L. and Reiners, T. (eds.) Gamification in education and business. New York: Springer. pp.1–20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-10208-5_1.

US National Archives (author on website) (2018) ‘Workshop participants enjoy national archives “escape room” experience’, National Archives News, 15 June. Available at: https://www.archives.gov/news/articles/workshop-participants-enjoy-escape-room-experience (Accessed: 21 February 2019).

Robin Sampson was formerly Assistant Archivist at University of the Arts London’s Archives and Special Collections Centre. His initial role was to establish and develop an institutional memory archive for UAL, documenting the institution’s formation and development. Whilst at UAL, his primary focus is to manage and preserve the ASCC’s archives and special collections for research, teaching and outreach. Robin has an interest in how archive collections can be gamified to create constructive and interactive approaches to learning.