Judy Willcocks, Head of Museum and Study Collection / Senior Research Fellow and Dr Alison Green, Reader in Art, Curating and Culture / Course Leader, MA Culture, Criticism and Curation, Central Saint Martins

This case study outlines the pedagogic, curatorial and museological practices that have influenced a long-term collaboration between the Central Saint Martins Museum and Study Collection and the MA Culture, Criticism and Curation course, which have led to the inclusion of a formally assessed Archive and Curatorial unit in the MA’s curriculum. The study draws on concepts such as experiential learning, object-based or object-centred learning and collaborative meaning-making. It summarises the practicalities of enabling students to work with uncatalogued archive material and addresses the complexities of formulating curatorial narratives from multiple perspectives. It also explores the criticality required to surface tacit knowledge and engage with curatorial practices.

archives; curation; object-based learning; experiential learning

In recent years, ‘criticality’ has become an important term, describing a mode of engaging with museums and archival collections. In 2006 a conversation hosted by Yale University Art Gallery involving the heads of eight university galleries and museums, argued that they should capitalise on their potential for ‘really radical critical thinking about not just objects, but modes of display’ (Hammond et al., 2006). That notion of the university museum as a laboratory for thinking, a space in which a provocation might be made, is at the heart of the pedagogic mission of the Central Saint Martins Museum and Study Collection, based at Central Saint Martins (CSM), a college within the University of the Arts London (UAL). The CSM Museum supports the university community through the delivery of object-led or object-centred learning activities and through a portfolio of in-depth, experiential, and group based projects. Following the principles of Kolb’s four-stage model of learning through experience (do, reflect, learn, test) (Kolb, 1984), the CSM Museum and Study Collection creates opportunities which allow students to engage with creative and professional practices.

The CSM Museum also acts as an institutional archive, recording the College’s rich history through the preservation of a wide range of documents from prospectuses and course handbooks to correspondence, photographs and administrative records. Since the college moved to a new campus at King’s Cross in 2011, it has been receiving considerably more archive material than curatorial staff have the capacity to catalogue. In response to this discrepancy between raw material and resources In Exchange (2011) was developed in conjunction with the BA (Hons) Fine Art course at CSM. The intervention explored the potential of working on uncatalogued archive material with students as collaborators on a live project. The pilot project involved students working with 45 boxes of uncatalogued material in a gallery setting, using the archive contents as a focal point for a series of public discussions and displays. The structure of In Exchange was then developed and honed to become a formally assessed annual ‘Archive and Curating unit’ on the MA Culture, Criticism and Curation (CCC) course, which addresses culture as a broad-based field, and was being planned and validated at the time that In Exchange emerged. Over the past six years the Archive and Curating unit has worked with collections belonging to the CSM Museum (for example, the Fine Art archive; Central Lettering Record; William Johnstone archive), as well as UAL’s wider resources, such as the holdings at the Archive and Special Collections Centre at London College of Communication (Charles Pickering, Lindsay Cooper and David Usborne collections) and several external lenders (such as the Southbank Centre and the June Givanni Pan-African Cinema Archive).

Learning from the managed chaos of ‘In Exchange’, the MA CCC project became more structured and closely supervised. The project begins with a short course of lectures and practical handling sessions, addressing the basics of museological and archival practice, along with the nitty gritty of cataloguing and object handling. The students are then introduced to their uncatalogued archive material, with which they work for a period of six weeks, filling out catalogue sheets, researching the material and formulating ideas for an exhibition in the college’s public window galleries. Archive or collection items must form the basis of the final display, but there are no restrictions on the exhibition’s form or concept, apart from the safety of the material, permissions and ethics. Each step of the process is managed by a tutor who is a qualified museum curator or archivist, as many of the students are new to museum processes and practices, and as a way of guiding students’ research and formulation of display ideas. Professional staff work alongside students to negotiate cataloguing conundrums, assess any handling or conservation issues that arise and suggest other areas for exploration and research.

The unit has led to many varied projects. Outcomes have included Idem (2014), a display exploring the emergence of practitioner identity within the art school through 1960s student records from Saint Martins School of Art. Another project, Eat. Drink. Print. (2014), visualised circles of influence in print industry dining clubs.

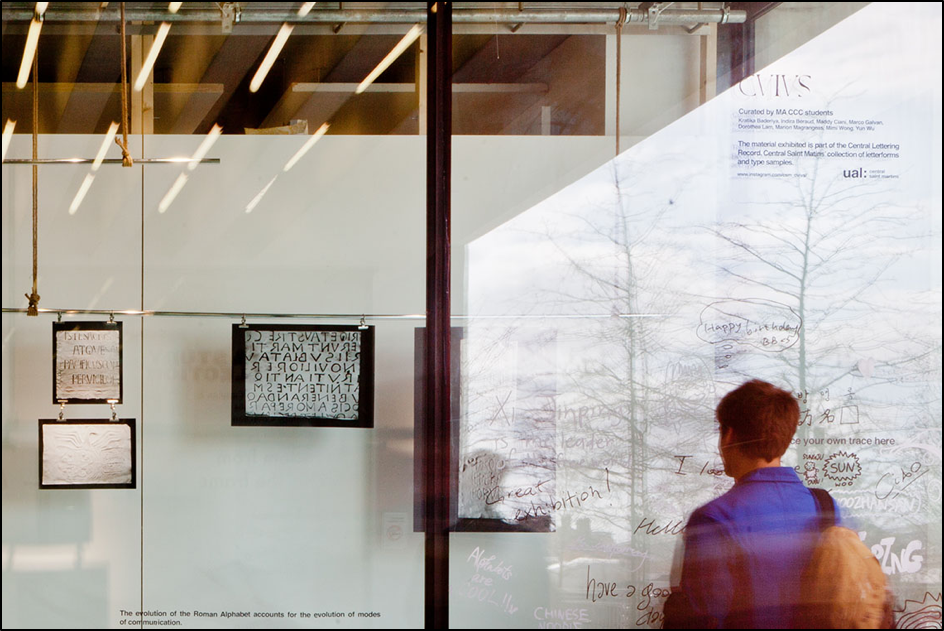

Pussy Power (2015) commissioned new artworks in response to the Teal Triggs’ graphic design archive. Where does this take you? (2016) was a display showing key works from the June Givanni Pan-African Cinema archive, an archive owned by a private owner. Most recently, Freedom from Within the Frame (2018) sought to represent the concepts of Basic Design through a curatorial conceit developed by two of Basic Design’s key advocates. CVIVS (2018) was a testament to the materiality of language through the mapping of Roman lettering squeezes from the Central Lettering Record.

The project contributes to MA CCC’s priorities, which are to combine academic and practical learning and develop students’ development as reflective practitioners. The ongoing value of this project is that it is ‘live’. Each year both the students and the material are new and each iteration presents an opportunity to challenge learning. We see it is an example of ‘continuous learning’ for students, tutors and lenders alike (Gibbs 1988; Larrivee 2000).

Another key objective for the CSM Museum, is using theories of object-hood to test the potential of working with diverse groups. Paris (2002) argues that meaning is not inherently held within an object or body of material; rather the transaction between the object and the viewer creates a space for meaning-construction. Hooper-Greenhill (2002) takes this one step further in her exploration of collaborative meaning-making, which extends theories of objects to the group dynamic. Following Hooper-Greenhill’s analysis of the ways museums construct knowledge through the display of objects, we can see the value of creating a space for students to experience and negotiate such issues, with all the complexities of a short time frame and a relatively large number of voices (as the groups usually range in size between seven and ten people). Rising to the challenge of formulating a curatorial narrative from multiple perspectives requires negotiation and compromise, and when it works well it can result in the communication of rich and complex ideas.

The process of curating also surfaces collecting policies and patterns of representation that are pointed out by Hooper-Greenhill in her critique of the putative neutrality of conventional museum narratives or the belief that objects ‘speak for themselves’. Hooper Greenhill also explores where meaning is generated, for and by whom. The concept of ‘pedagogy as culture’ (Hooper-Greenhill, 2002, pp.124-126) is central to the way we explain and facilitate the students’ task of making meaningful displays with their given material. Moreover, her active shifting between theoretical frames (such as Michel Foucault’s concept of knowledge/power) and practical ones (by examples) mirrors the broader approaches taken by MA CCC in teaching students.

At the conclusion of the project students submit a critical report outlining their contribution and charting their developmental journey. The reports (which are formally assessed) are a key tool for developing the students’ capacity for reflective practice. Almost all attest to the challenges of working in relatively large groups to identify a strong curatorial narrative. To quote one participant: ‘One of the central learning curves in this process was moving towards a sense of shared ownership of ideas, rather than holding on to thinking of our individual contribution in terms of ’I’ or ʻmyʼ’ (student report, Willcocks and Green, 2016). In another, report one of the students observed that:

Overall the project was […] extremely challenging and […] taught me how institutions deal with certain matters concerning identity and ownership, and how to go around it [in an] elegant manner. Working with a big institution was very valuable and enriching experience [and] working in a group was extremely pleasant, as you can learn and collaborate on ideas, which is extremely important in any work environment.

(student report, Willcocks and Green, 2016).

From a museological or archival point of view there are clear benefits. These include: the completion of catalogue records to provide better future access; the exploration and public exhibition of previously unseen material; and the reimagining of collections through the eyes of a diverse and international student body. For the students, who undertake the archiving unit right at the start of their course, the excitement and pressure of being able to tell stories around previously un-researched archive material is a high-stakes ice breaker.

There are also challenges to be faced, particularly when borrowing material from external bodies. All material, whether from UAL’s archives or on loan from external partners, is handled and displayed with care and consideration and in a manner that is conversant with museum standards – a set of restrictions which can clash with students’ aspirations for display. The student curators also face real-world issues such as sensitive personal data, copyright and intellectual property, and discover – through research – the ‘living’ stakeholders who may not be obvious when initially looking at boxes of documents. Engaging with those represented in the archive makes for very authentic curating experiences, but those relationships can have elements of tension when dealing with material that has been borrowed from an external partner who will have their own perceptions of institutional reputation to maintain.

Examples of these complex encounters and issues are wide ranging. From the joys of tracking down, contacting and interviewing artists, film makers and teaching staff about events that took place half a century ago to frustrated attempts to ‘recreate’ a past member of Southbank Centre staff through current social media accounts. When the Southbank Centre communications team expressed concern at the proposal and vetoed the notion of engaging with a live Twitter exchange with the faked online persona, eleventh hour negotiations resulted in the creation of a display offline. While this was disappointing for the students they were offered a platform to showcase their work at the Royal Festival Hall, showing how working creatively with partners can lead to new opportunities. Another point of frustration was encountered by students engaging with the June Givanni Pan African Cinema Archive, who were required to liaise with all artists represented in the archive through June Givanni herself – a process they thought unnecessarily time consuming but one which reflects the sensitivities of working with an archive that represents an individual’s life work and professional connections.

The exhibitions that have resulted from the collaboration between the CSM Museum and Study Collection and MA CCC have resulted in exhibitions that are radically different from what might have been proposed or realised by museum staff. In part, this is due to the disciplinary training of museum curators and archivists, who are also subject to inevitable institutional lenses and priorities that influence the way they view the collections with which they work. The students are also diverse in various ways. They come from different disciplinary backgrounds: not only Fine Art and Art History/Museum Studies, but from disciplines across the humanities and social sciences as well as various art and design practices. The international nature of the cohort also contributes in myriad ways to the development of each project, as differences emerge in working practices, cultural perspectives, languages, interests and forms of expression.

When running a unit such as this, which balances the preservation of varied artefacts with a desire to foster creative responses, the challenge is to maintain space in the project for learning, creativity and experimentation. During the sessions, we emphasise that these are ‘pedagogic’ projects, as a way of signalling that some things are agreed at the start but others are left open to the process. The objective is to create an arena – professional and real – for students to work in. The effect is usually a powerful buzzing tension around open-ness to process, risk, creativity, comportment, interdependence, and the potential for future professional identity. Such projects need to be seen as ‘special cases’ and not commissions, something like research, knowledge exchange, and practice-development in one. It must be acknowledged that the archive project is time consuming and takes up many staff hours, but the benefits of throwing open the collection in this way offers huge opportunities for both the museum and the students involved.

Chatterjee, H. and Hannan, L. (eds.) (2015) Engaging the senses: object-based learning in higher education. Farnham: Routledge.

Chatterjee, H., Duhs, R. and Hannan, L. (2013) ‘Object-based learning: a powerful pedgogy for higher education’ in Boddington, A., Boys, J. and Speight, C. (eds.) Museums and Higher Education Working Together: Challenges and Opportunities. Farnham: Routledge, pp.159–168.

Engeström, Y. (1999) ‘Activity theory and individual and social transformation’ in Engeström, Y., Miettinen, R. and Punamäki R.L. (eds.) Perspectives on Activity Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.19–38.

Gibbs, G. (1988) Learning by doing, a guide to teaching and learning methods. London: Further Education Unit. Available at: https://thoughtsmostlyaboutlearning.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/learning-by-doing-graham-gibbs.pdf (Accessed: 1 March 2019).

Hammond, A., Berry, I., Conkelton, S., Corwin, S., Franks, P., Hart, K., Lynch-McWhite, W., Reeve, C. and Stomberg, J. (2006) ‘The role of the university art museum and gallery’, Art Journal, 65(3), pp.20–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043249.2006.10791213.

Hooper-Greenhill, E. (2002) Museums and the interpretation of visual culture. New York: Routledge.

Kolb, D.A. (1984) Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Larrivee, B. (2000) Transforming teaching practice: becoming the critically reflective teacher’, Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives, 1(3), pp.293–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/713693162.

Lea, M.R. and Street, B.V. (1998) ‘Student writing in higher education: an academic literacies approach’, Studies in Higher Education, 23(2), pp.157–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079812331380364.

Paris, S.G. (2002) Perspectives on object-centred learning in museums. Mahwah: Routledge.

Shreeve, A., Sims, E. and Trowler, P. (2010) ‘ “A kind of exchange”: learning from art and design teaching’, Higher Education Research and Development, 29(2), pp.125–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360903384269.

Willcocks, J. (2015) ‘The power of concrete experience: museum collections, touch and meaning-making in art and design pedagogy’ in Chatterjee, H. and Hannan, L. (eds.) Engaging the senses: object-based learning in higher education. Farnham: Routledge, pp.43–56.

Willcocks, J. and Green, A. (2016) Student report. Internal UAL Report. Unpublished.

Judy Willcocks is an Associate of the Museums Association with twenty years’ experience of working in museums, and has a long-standing interest in developing the use of museum collections to support teaching and learning in higher education. Judy runs the Museum and Study Collection at Central Saint Martins and teaches an archiving unit for the College’s MA in Culture, Criticism and Curation. Judy is also interested in developing relationships between universities and museums in the broader sense and is the co-founder for the Arts Council funded Share Academy project, exploring the possibilities of cross-sector partnerships.

Dr Alison Green is a Reader in Art, Curating and Culture at Central Saint Martins, where she is Course Leader of MA Culture, Criticism and Curation and Senior Lecturer on BA (Hons) Culture, Criticism and Curation. She is a PhD supervisor and active member of University of the Arts London's research and teaching community. Alison is an art historian, critic and curator with a strong history of publications, public talks, exhibitions and conference participation. Her current research is about socially-engaged art and curating in a (post-) global context relating to ethics of representation, economy and ecology.