Alexandra Lumley, Associate Dean of Academic Support, Library and Student Support Directorate, and Chris Lloyd, Associate Director of Planning: Management Information, University Central Planning Unit, University of the Arts London

This article presents initial analyses of degree attainment data, which reveal important questions surrounding writing for academic and other purposes in creative arts education. It reflects on phase one of an ongoing exploratory enquiry into the relationship between assessed writing and undergraduate attainment of first class and 2.1 as the final grade of the degree. Prompted by students’ increasing requests for support in ‘academic’ writing, this study was initiated within a project at the University of the Arts London, addressing the lower degree attainment levels of UK ethnic minority and International students compared with white British and home/EU students. By identifying genres within assessed writing and their impacts on students’ grades, the study revealed the complexity of writing as a factor in attainment in creative arts, suggesting areas for further enquiry.

creative arts curricula; attainment differentials; writing genres; assessment; academic support

This article presents an exploratory enquiry into the relationship between writing in creative arts curricula and student degree attainment. The study considered students’ final degree grades from undergraduate (UG) courses across the six constituent colleges of the University of the Arts London (UAL), and the diversity of assessed writing across subjects including design, fashion, fine art, media and performance. Writing in many forms is an integral part of professional arts practices and has significant presence throughout UAL’s courses.

Undertaken collaboratively at University level by the authors (senior managers of Academic Support and of Management Information), this enquiry is one of many actions at UAL to deepen understanding of evident inequities in student achievement and address them. An increasing student demand for support with ‘academic’ writing gave impetus to the study, leading to the need for an evidence base, an exploration of data to determine factors affecting unit/module level achievement. This article surveys findings and poses questions arising in phase one of the study, undertaken between May 2017 and May 2018. Starting points were twofold: an analysis of assessed written components in curricula as documented in course handbooks, and three years of final degree grade (attainment) data. Whilst focused on assessed writing, we recognise complex wider factors impacting on student attainment, including students’ diverse experience and circumstances, curriculum content interrelationships, staff diversity, and approaches to teaching, support, assessment and degree classification.

With the aim of creating a more nuanced lens through which to approach and interpret the relationship between writing and student attainment, this article references other studies, recognising an extensive literature beyond its scope. Much research and debate regarding writing in Art and Design Higher Education (HE) has been spearheaded by the ‘Writing Purposefully in Art and Design’ (Writing PAD) project and network, led by Goldsmiths, University of London, since 2002. An aim of that project was to promote ‘inclusive approaches to the purposes and possibilities of writing’, anticipating this would impact on ‘debate surrounding […] assessment criteria’ (2003, p19). The rich complexity of the writing dimension - its history and interactions with speaking, drawing, making, with social media usage and electronic literature - and not least ongoing debates regarding critical theory and development of the disciplined mind (see the literature of Writing in the Disciplines, University College of Cariboo, 2001) - is acknowledged in this study. However, we have resisted many possible approaches in order to focus first on establishing some potentially firmer ground by creating data-based evidence.

That said, the main methodological position is one of enquiry, and the approach to data is interpretative. The article will provide context, explain the dataset build, consider findings and pose questions that have arisen in the process, aiming to provoke further thought about student writing from perspectives such as inclusivity, theory/practice in course design, academic literacy/support, assessment and awarding systems, and graduate futures.

Both the attainment ‘gap’ or ‘differentials’ data of UAL, and the experience of our Academic Support provision provoked this study. When speaking of the lower achievement of some groups of students compared with others, the term ‘attainment gap’ is commonly used across UK universities. The Equality Challenge Unit (ECU) articulates a definition: ‘[the] degree attainment gap is the difference in “top degrees” – a First [1st] or 2:1 classification – awarded to different groups of students. The biggest differences are found by ethnic background’ (ECU, 2018). The term is contested by some as it may imply a deficit in students’ abilities, as opposed to perceived inequalities/injustices in educational provision experienced by different groups of students, for example through white western dominated curriculum content.

As exemplified by the ECU’s description, analyses of degree attainment differentials often focus upon the disparities between students of different ethnic backgrounds. In the UK the generalising acronym for Black and Asian Minority Ethnic, ‘BAME’, is controversial. As Sandhu presents in a recent report for BBC news, it is unacceptably reductive, particularly if associated with individual identity (2018), as is the grouping of ‘International’ students, meaning any students of non-EU nationality. In this study we use these terms as general grouping names, conscious of the diverse and intersectional identities and experiences that they comprise. Comparison of the attainment of groups within ‘BAME’ and ‘International’ is a future aim.

At UAL, attainment differentials are evident between Black and White UK Home students, between International and UK/EU students, and between UK Home students of lower and higher socio-economic classes (based on numbered parental occupation groups, 1-3 being higher and 4-7 lower, declared on students’ degree applications). The Socio- Economic Class (SEC) differential between groups was relatively small at 5.6% in 2016/17 and the International compared with Home student attainment narrowed from 17% in 2015/16 to 14.4% in 2016/17 but the disparity between Home BAME and Home White students is most intractable at 21.7% in 2016/17, despite overall improvement in BAME students’ attainment (UAL, 2016; 2017a). This study aimed to contribute insight to possible causes of these differentials at UAL and challenge ourselves to change the situation.

Two previous relevant studies, undertaken at UAL’s London College of Fashion (LCF), have called for further research at university level. Both addressed attainment, highlighting the complexity of variables, anecdotal and qualitative evidence as well as data constraints. One looked at LCF data 2007-2011, examining Home students’ final grades in the Cultural and Historical Studies unit/module that complemented the creative curricula (Herrington, 2015). Herrington’s report plus unpublished investigations at Central Saint Martins (CSM) (2012) concluded generally positively regarding the impact of units/modules in cultural studies or equivalents, comparing UK BAME and white students’ grades. The other considered LCF data 2012-2015 in relation to Home BAME students’ use of Academic Support (Panesar, 2017) referred to below.

Academic Support teams in UAL colleges are dedicated predominantly to developing students’ research, critical thinking and writing abilities across all courses (working with course lecturers, language tutors and librarians). Qualitative feedback has continued to highlight demand for further support for academic writing, referencing, and especially for ‘dissertation’ in the final year, where unit/module grades at UAL currently define the degree classification. Comments in the National Student Survey (NSS) and in termly dialogues between student representatives’ and College Deans have reinforced this demand. It cannot be unconnected that comparatively higher numbers of International students (who, excluding EU, comprise 32% of UAL undergraduates) (UAL, 2018) become entangled in academic misconduct, such as plagiarism or failing to accredit sources. Academic Support is under pressure to respond to these needs whilst resisting assumptions of student deficit, working to enable and empower students, not to provide fixes. This is not an easy balance to achieve. As Panesar has noted, ‘some […] university staff maintain the idea of a BAME student skills deficit that tends to point towards academic support as a form of salvation’ (2017, p.45).

Across UAL, Academic Support engages with about a third of all UG students in face-to-face sessions - 32% in 2016/17 (UAL, 2017b), giving considerable insight to the support needs of a significant proportion of the student body. It is a positive sign of the reach and efficacy of the provision that higher percentages of students from all demographic groups who attend Academic Support attain 1st/2.1 than those who do not (UAL, 2017b). Language and Academic Support teams identify many factors contributing to student anxiety around writing – from International English Language Testing System (IELTS) scores, which are required for admission to courses, through to prior learning experiences and concerns about valid academic discourses in different disciplines (tacit beliefs), to how assessment of writing ‘works’. Sabri has noted that when ‘students perceive assessment to have been unjust, they locate the problem in the shortcomings of the support they received before submission […] some students also believe the assessment process itself is unfair and influenced by tutors’ favouritism, and personal or professional interests’ (2017, p.2). Inconsistency in expectations, assumptions, and tutors’ knowledge can all influence outcomes for students of diverse backgrounds.

Creative arts qualifications hover in a liminal space, historically relating closely to both industry and culture. Taking Ryle’s epistemological differentiation of ‘know how’ and ‘know that’ (1949), creative arts combine the languages of vocational ‘talent’ and technical know-how on the one hand, and academic ‘study’ and scholarship on the other. Vocational or professional education is often differentiated linguistically, counterpointed with or side-lined by the ‘academic’ literature, whilst the world of HE is ‘academic’ by definition: thus ‘writing’ often defaults to mean ‘academic writing’ only.

In their 2012 large-scale survey of British Academic Written English (BAWE), Nesi and Gardner define five social functions of student writing: ‘demonstrating knowledge and understanding’; ‘critical evaluation and developing arguments’; ‘developing research skills’; ‘preparing for professional practice’; and ‘writing for oneself and others’ (Nesi and Gardner, 2012, p.36-43). Their extensive study of genres across disciplines does not include creative arts but it positions ‘preparing for professional practice’ firmly within the ‘academic’ frame. When we speak of ‘academic writing’, do we mean this, as opposed to other genres of writing, or say this just because we are in a university?

Discussions about ‘written’ work as opposed to the ‘creative’ often align with ‘theory’ and ‘practice’ respectively, as if writing were not a practice, creative or otherwise, and implying that theory is not discernible through other forms. Lockheart, speaking at a UAL Teaching Platform event (2017) identified how the position of written work in the UK Art and Design sector has been influenced by misreadings of the 1960 and 1970 Coldstream Reports. In the latter, Coldstream elaborated on the recommended 15% ‘history of art and complementary studies’ requirement in the Diploma in Art and Design (the equivalent of a BA in the UK today). Significantly, there is no mention of writing as the mode of assessment (Coldstream/NCDA, 1970, paragraphs 34–41, p.10-12).

Understandings of writing’s purposes and power in a ‘higher education’ are wide-ranging: for example, that contextual knowledge and critical theoretical argument are best evidenced (or most easily assessed) through written outputs; that writing is an essential communication skill in professional and academic contexts; that writing is intertextual, building knowledges; and that writing as a process develops critical thinking to create reflective practitioners. ‘Thinking-through-writing to further the greater good’ (2018) is the mission of Writing PAD, while Pat Thomson, Professor of Education, University of Nottingham, identifies seven threshold concepts for academic writing on her blog: ‘academic writing does “work” – for instance it can persuade, excite, reassure the reader’ (2018). In designing curricula to include writing at different stages, are we expecting student learnedness (knowledges) to be represented through writing, professional skills to manifest in writing (research, argumentation, documentation methods) and/or learning to occur by writing (reflective and evaluative practices)?

Writing is a culturally meaningful product in itself with socially (and institutionally) constructed powers. As established by Lea and Street in the 1980s/90s, the Academic Literacies model subsumed ‘study skills […] student writing as technical and instrumental skill [and] academic socialisation […] [proposing] student writing as meaning making and contested’ (Lea and Street, 2000, p.34). Referencing Bourdieu’s concepts of habitus and cultural capital, Singh and Cowden highlight the capacity issues for Black working class students ‘to see themselves as intellectually capable beings’, and challenge ‘a pernicious conception of intellectuality being a quality represented by “superior” intelligence or “giftedness” […] [the] subjective sense of intellectuality […] being crucial to the learning process is itself a form of cultural capital’ (Singh and Cowden, 2016, p.89-90).

Status anxiety about intellectuality in the creative arts might block the ability to see students’ potential as creators of knowledge and shapers of industries in new ways, leading accidentally to inculcation rather than exploration, to pursuit of academic kudos rather than meaningful work. Are academic written assignments set without questioning their relevance to students’ development and directions?

‘Re-genring’, as explained in the Journal of Writing in Creative Practice, enables students ‘to shift academic material from one genre to another, for instance an essay into a play [to explore] disciplinary knowledge from different perspectives, drawing on the different communicative resources and opportunities that different genres afford’ (English and Groppel-Wegener 2018, p.4). In the same volume, Camp and Foster define Fine Art ‘practice’ as ‘a synthesis of four genres – studio work, reflective journal, research tasks and academic essay’ (2018, p.107), encouraging ‘students to see critical writing as an important facet of their practice’ (p.100). Such explorations across genres and integration of writing into studio practices can make it an accessible, meaningful and hopefully transformational activity for all students.

Determining if the challenges students experience in undertaking academic writing carries through to lower attainment (1st/2.1 classifications) meant building a dataset and examining assessed writing requirements. Units/modules that comprise the final year (level 6) of all the creative arts undergraduate degrees at UAL include a ‘dissertation’ and/or other types of written and studio work. The main aim was to ascertain if under achievement in written submissions contributes to overall degree attainment, and in any patterns or specific contexts across the student groups.

An analytical comparison of assessed types of work and grade outcomes involved collecting and categorising assessment data. Achievement in earlier written components might be studied at a later stage, to discern any relationships with ultimate attainment: data collection therefore included unit/module results at the lower levels, 4 and 5, the first and second years of the three-year degree as well as level 6, the final year. Data was extracted from the UAL student records system for 2013/14, 2014/15 and 2015/16 (the latest data available at the outset of the study, at May 2017) making a dataset of almost 150,000 unit results. Student groups included fee status, UK ethnicity and socio-economic class and subject groups covered all creative arts UG courses at UAL (explained below) across all three levels.

The nature of ‘written’ and other outputs across all units of the courses was then established. As the number (88) of distinct UG courses across UAL’s six colleges all require writing in nuanced disciplinary contexts, unit/module specifications in all the relevant course handbooks were used to identify assessment ‘requirements’ or ‘evidence’. These revealed an extremely wide range of approaches and expression, although descriptions of written submissions did not vary particularly by subject: the ‘language’ of Fine Art or Fashion for example would probably be more visible in assignment briefs than in course handbooks which tend to have a more formal tone.

Drawing on the framework developed by Nesi and Gardner (2012, p.29), we identified five genre families of assessment evidence/requirement:

The process of division under these headings involved fine judgment calls, as descriptions were often composite or ambiguous in expression. For the purposes of analysis, we focused on ‘written assignments’ and ‘studio outputs’. ‘Studio outputs’ included bodies of ‘practical’ work, final projects/shows, and industry projects/completion of placements.

‘Written assignments’ were sub-divided to form three genre families:

The three genres of written assignments along with studio outputs’ (‘practical’ work) formed our ‘assessment types’ and were cross-referenced to eleven standard UAL subject groups:

Three other subject groups were excluded at this stage as they had more written than ‘studio’ type outputs, which could potentially skew analysis: Business and Management and Science; Curation and Culture; and Journalism, PR, Media and Publishing.

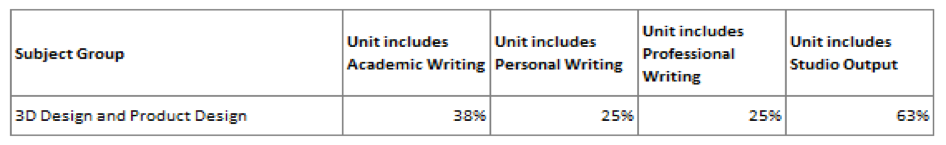

The proportions of units that included each of the assessment types were calculated for each of the 11 subject groups. Where units included more than one assessment type (e.g. studio output and professional writing) the grades for such units were used in the calculations for each assessment type. Academic and personal writing were both in about a third of all level 6 units, while only a quarter of units assessed professional writing. However, these proportions varied greatly across the subject groups, and need to be considered further, for example in relation to the weighting given to units that contribute to the final award.

The findings of the comparative analysis discussed at this stage relate to level 6 (final year) units. As noted above, data is available for levels 4 and 5 (first and second years) for future study. Commentary has prioritised Home BAME and International attainment differentials (the difference in proportions of student groups achieving a 1st/2.1) which are most pronounced at UAL, over Socio-Economic Class (SEC) - although this is represented in our data and the charts below.

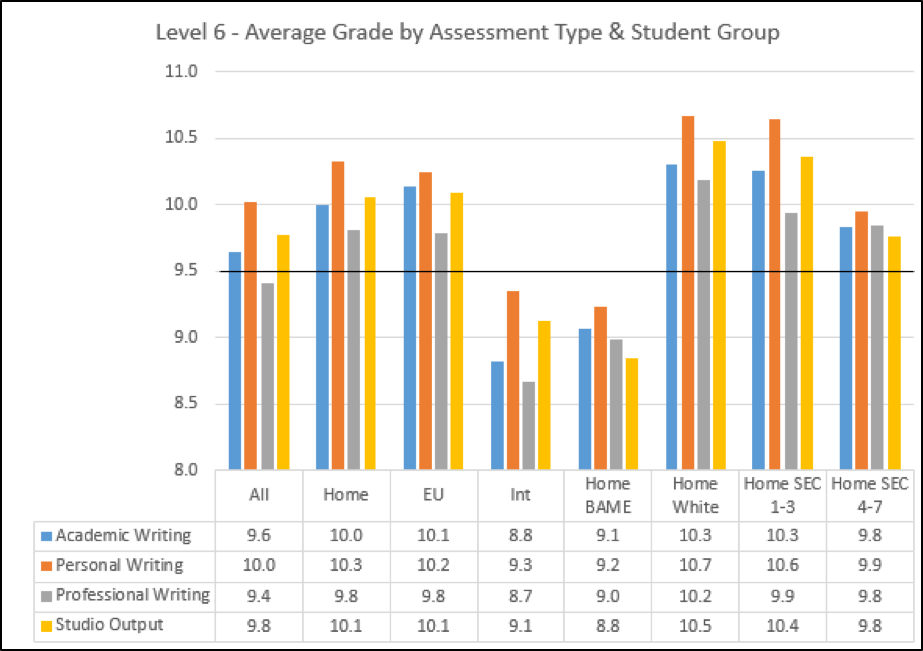

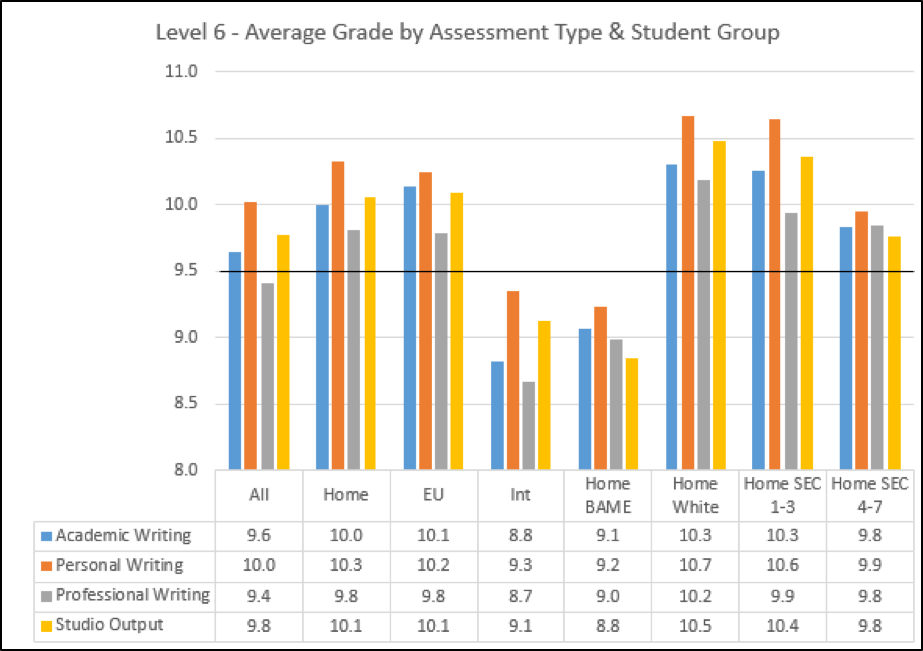

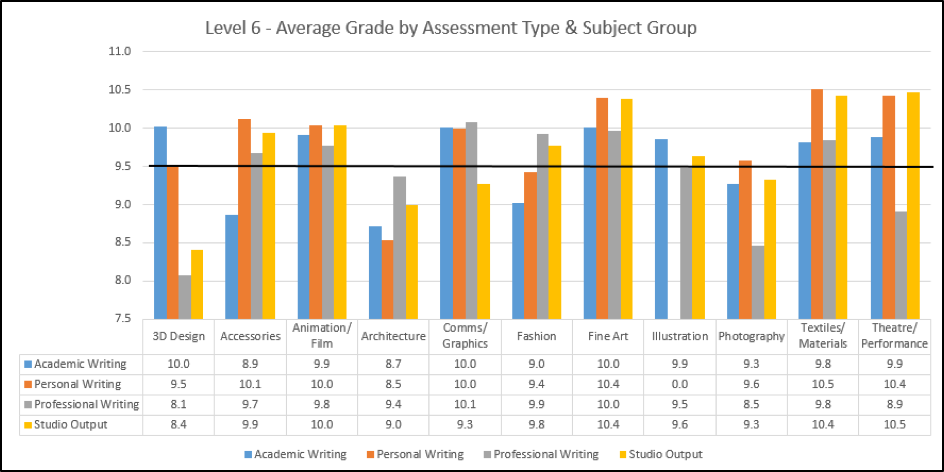

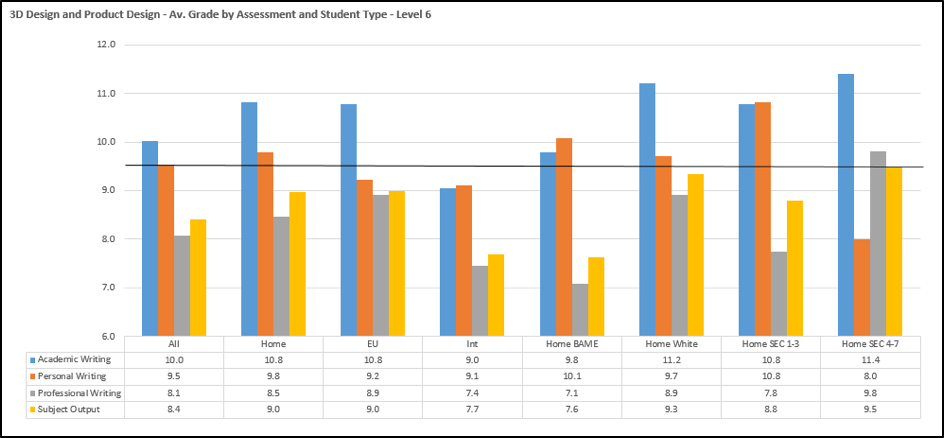

At UAL, a 15 point scale is used to calculate degree grades and classifications, converting letter grades given in unit assessment to numbers. The highest grade A+ is equivalent to 15 points, A is 14, A- 13, B+ 12, and so on down to the lowest, F- at 1 point. Having converted each student’s level 6 unit grades to points, these ‘scores’ were totalled for each student group (fee status, Home ethnicity etc.) and each of the 11 subject groups, and then averaged to calculate the mean score for each group. The left axis of the charts in Figures 1, 2 and 4 below indicate scores and hence classifications: the threshold between a 2.1 and a 2.2 is 9.5 points, indicated by a line in the charts.

Figure 1 (below) shows the average grades for student groups highlighting their variable performance in level 6 units containing different assessment types.

The average grades of International and Home BAME students’ are below the 2.1 threshold for all assessment types. For BAME students the lowest average grade occurred in units containing studio outputs. International students’ averages showed more variation than BAME, with units containing personal writing half a grade higher than for other types of writing. For both BAME and International students, personal writing achieved the highest average grade followed by academic and professional writing. For all student groups, units with at least one assessed written component produced the highest average grade. Units containing personal writing produced the highest average grades across the board. Average grades in units containing each assessment type were then considered across subject groups, for all students. Figure 2 (below) summarises this.

Wide variations are immediately visible across and within the subject groups, making it impossible to perceive patterns. There was no consistent correlation between the prevalence of assessed types of writing in a subject group and the average grade level generated. For example, in Fashion less than a quarter of units contain assessed professional writing, yet these units showed the highest average grade.

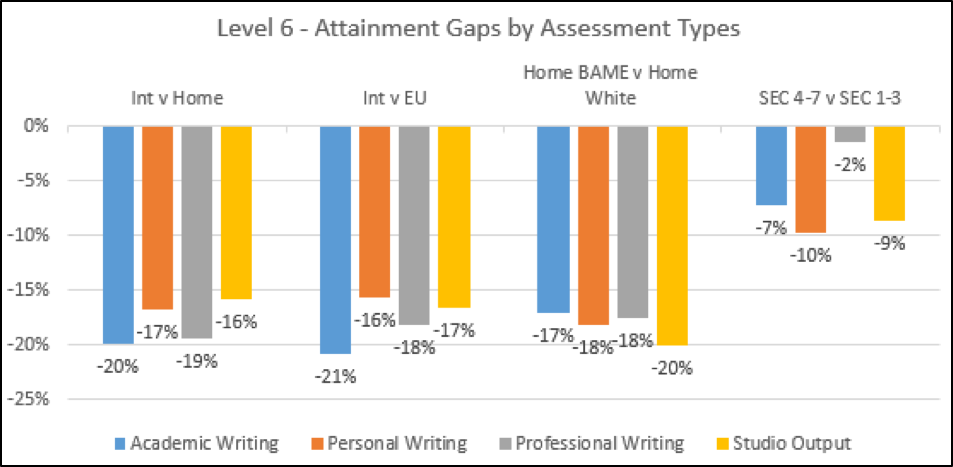

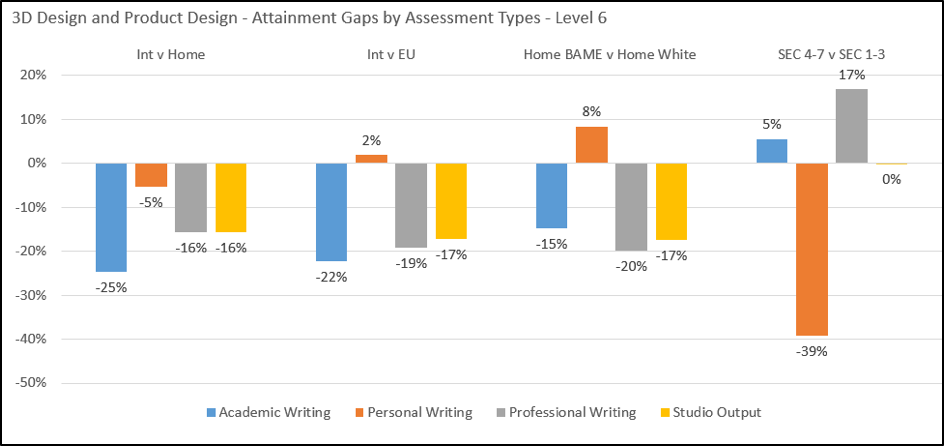

We then looked at attainment differentials. Figure 3 (below) shows comparative pairs, with the percentage difference between them. For example, the gap between International and Home students’ attainment in level 6 units containing academic writing is 20%.

Academic writing produced the largest differential for International students relative to other forms of writing, but within the groups of significant differential (International and BAME) variations were slight. No one type of writing appears to contribute more than another to the attainment gap between BAME and white students: academic writing produces a marginally smaller differential than studio outputs.

A data summary for each subject group was also produced. These state the proportion of units that included each of the assessment types, and show the average level 6 grades by student groups, plus attainment differentials by assessment types; they also provide some analysis to prompt consideration by courses in the subject group. The 3D and Product Design subject group summary including Table 1 and Figures 4 and 5 is provided (below) as an example.

For the 3D and Product Design group, the data suggests the following for consideration:

Study of the data on student attainment in relation to assessed written components generates questions regarding how such work is positioned, perceived and supported within UAL. Discussion below reflects further on the findings suggesting areas for exploration.

A reading of unit/module descriptors in the course handbooks indicated nuanced purposes and positions of writing across design, media, fashion, the applied, performing and fine arts, but more noticeable variation by college ethos and approach. Descriptions within course handbooks ranged from a few words to paragraphs, with evident uncertainty about genres and forms that relate to academic, professional or personally reflective purposes. Nesi and Gardner note ‘any problems with the assessment process are less likely to arise because of intransigence on the part of participants, and more likely to be due to failure to adequately explain the nature of the relevant assignment genres’ (2012, p.17).

‘Glossaries of terms’ included in course handbooks also reveal disparities and surprisingly slight and conventional definitions. Continuity of definition, some consistent language, whether discipline specific or commonly agreeable at any level, regarding terms such as ‘research’, ‘project proposal’, ‘case study’, ‘rationale’, and ‘methodology’ amongst others, could be beneficial to students and staff alike. However, glossaries are problematic in that meanings are contextually made and reinvented, particularly since universities encourage contestation by nature, especially when defining disciplines. Despite this, in the interests of transparency and given the diversity of UAL students’ entry routes and backgrounds, glossaries of genre-related terms within subject groups could be supportive. Can students’ discovery of contextualised and contested meaning be scaffolded, whilst not constrained?

The integration of theory and practice and value of openness in some courses allows students to demonstrate learning across a range of assessment evidence without ascribing it to genres or pre-defined forms. Descriptions can thus become minimal, ambiguous and less graspable: for instance, requiring ‘a written piece’ may intend to ensure inclusivity but its generic and imprecise nature seems unhelpful. Language tutors at UAL have asked ‘whether [use of personal voice] is personal stylistic preference on the part of degree tutors or whether it is a specific feature of the […] discourse community. It may also result from general (mis?) perceptions of what constitutes acceptable academic writing’ (King and Hickey, 2017, p.212). Does unclear articulation of expectations about writing cause confusion for students?

Higher average grades were found in units containing personal writing, which could be attributable to their integration with studio work. Further research could indicate that ‘lower performing students are more likely to benefit most from an opportunity to reflect on their intellectual capability, both in terms of self-perception and behaviour, than high-performing students who may already possess relatively high levels of self-belief in such traits’ (Singh and Cowden, 2016, p.93). Creative students may have greater aptitude for self-reflection than for academic research and analysis, or this may vary across arts and design disciplines. Are hidden criteria or the unconscious biases of academic staff influencing the assessment of types of writing? Are we harsher when assessing professional writing than the academic or personal, or are students not seeking support for it?

Historical/theoretical/contextual/cultural studies aspects of courses are structured differently across the colleges of UAL, either embedded in programmes or co-ordinated across them. Academic writing tends to be assessed by tutors from these curriculum areas, even when assessed work is integral to students’ studio practice. Herrington explores the anonymous procedures staff use to mark essays, suggesting this could be ‘a reason for the comparative success of minority ethnic students on theory-based units […] staff who are involved in conversations around content are unlikely to mark them’ (2015, p.163). To what extent is our use of anonymous marking affecting attainment?

Turner asserts that ‘writtenness is an ethical issue. Its fluctuating role is a source of inequitable treatment for students […] rigorous requirements may be demanded of some students but not of others, and its role in assessment processes is seldom fully explicit’ (2018, p.198). Further enquiry is needed regarding how different assessment cultures and practices impact diverse student groups. The number of assessed components pro-rata to credit size of a unit may affect the attention students give to a written assignment; the effects of individual submission weighting within units compared with units assessed holistically, and the different sizes and balances of dissertation and studio components in final awards require further study.

In Academic Support at UAL much time is spent with students clarifying linguistic confusions, decoding terms and restoring internal logic to written assignment briefs where this has been lost, before any processes of writing, fears, misconceptions, motivational and time management issues are addressed. As Lockheart has observed, ‘dismissing writing only makes it more frightening for students’ (2017). De-mystification of writing is essential, to be achieved without over simplification or pretending that writing is the same as studio work: writing is rarely the only component of a student’s creative arts practice.

UAL Academic Support adopts design and making strategies, practical materials and familiar disciplinary terms to alleviate fears of writing; for many students, writing has a hierarchical or irrelevant position in relation to their subject and needs to be re-presented as a meaningful and approachable dimension of enquiry-based practice. As Murray outlines, ‘writing involves both deciding in advance what to say and discovering what you want to say as you make choices about how to say it’ (2005, cited in Turner, 2018, p.156).

Academic Support teams aim to expand student understanding of the stepping stones to writing, especially major texts such as dissertations. Preparatory academic reading is interpreted largely as an independent learning activity, ‘an arduous task, leading to panic and confusion and a vortex of lost time as the student is overwhelmed by the attempt to understand and to weigh the validity of opposing ideas’ (Howell-Richardson and Ganobcsik-Williams, 2016, p.151). Would more emphasis on reading (which feeds research) and on speaking (which feeds debate) lead to stronger writing outcomes?

In the ‘creative industries’ (as well as education, medicine/health, law, business etc.) listening and speaking as well as writing purposefully are paramount to professional practice. In education ‘communication is not simply for talking about practice but also a vital way of carrying out practice’ (Hoadley-Maidment, 2000, p.170). The emergence of lower average grades in units containing professional writing has prompted greater collaboration between Academic Support and Careers and Employability at UAL. In creative arts HE greater value could be placed on writing for professional purposes and understanding this as part of academic and creative practice for students.

Overall, the data analyses indicate some surprising conclusions, primarily that academic writing, whilst a notable negative differential for International students, is neither adversely nor positively affecting grades, contrary to some expectations prior to this study. Studio outputs were expected to impact grades more positively. The fact that the average grade results in units involving personal writing components are generally higher and units containing professional types of writing lower is of interest, as has been discussed. However, contradictions across subject groups abound and the weightings of final award components need to be recognised. The provision of data for levels 4 and 5 create a starting point for courses to reflect on how written components are realised throughout their curriculum.

Student feedback around feeling insufficiently prepared for dissertation or equivalent written work at level 6 urges re-consideration of pedagogies and curriculum content at earlier stages in courses. Developing reading, research, listening, speaking and writing abilities within and through creative practices is core and not just a matter of additional support. The evidence base should stimulate exploration and exchange of ideas and practices to support areas where rethinking approaches to writing in the curriculum could actively redress attainment and awarding differentials.

Herrington highlighted the positive learning space afforded by the theory-based unit at LCF, citing student comments on the ‘opportunities to discuss identity and to question all cultural construction…engaging cultural capital.’ (2015, p. 164). The uncertain or unexplained meanings of the varied names for historical and theoretical aspects of the curriculum, and the terms in use describing assessed writing should be clarified in the interests of inclusivity.

The process of establishing and interpreting this evidence base to enable study of the potential impacts of assessed writing on student attainment at UAL has surfaced many questions. The data may help provide an initial basis, amongst the anecdotal evidence, myths and beliefs, incentivising more forensic explorations of extremely complex realities for courses, regarding the role of writing in student attainment.

Permission to utilise UAL data for this publication was given by Stephen Marshall, University Secretary and Registrar, University of the Arts London.

Camp, S. and Foster, K. (2008) ‘Hollowed-out genring as a way of purposefully embracing troublesome knowledge: Orientation and de-orientation in the learning and teaching of fine art’, Journal of Writing in Creative Practice, 11(1), pp.99–120. https://www.doi.org/10.1386/jwcp.11.1.99_1.

Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London (2012). UG achievement in contextual studies units. Internal Report. Unpublished.

Coldstream, W. (1970) The structure of art and design education in the further education sector report of a Joint Committee of the National Advisory Council on Art Education and the National Council for Diplomas in Art and Design. London: HMSO.

English, F. and Groppel-Wegener, A. (2018) ‘The chicken editorial: Which comes first(?)’, Journal of Writing in Creative Practice, 11(1), pp.3–11. https://www.doi.org/10.1386/jwcp.11.1.3_2.

Equality Challenge Unit (2018) ‘Degree attainment gaps’, ECU Guidance and Resources. Available at: https://www.ecu.ac.uk/guidance-resources/student-recruitment-retention-attainment/student-attainment/degree-attainment-gaps/ (Accessed: 25 July 2018).

Herrington, E. (2015) ‘Knowing people as individuals: Academic attainment in art and design’ in Hatton, K. (ed) Towards an inclusive arts education. London: Institute of Education Press, pp.153–169.

Hoadley-Maidment, E. (2000) ‘From personal experience to reflective practitioner: Academic literacies and professional education’ in Lea, M.R. and Stierer, B. (eds.) Student writing in higher education. Buckingham: SRHE and OUP, pp.165–178.

Howell-Richardson, C. and Ganobcsik-Williams, L. (2016) ‘Mixing metaphors for academic writing development’ in Steventon, G., Cureton, D. and Clouder, L. (eds.) Student attainment in higher education: Issues, controversies and debates. Abingdon: Routledge, pp.144–158.

King, D.C. and Hickey, H. (2017) ‘Creating and using corpora: A principled approach to identifying key language within art and design’ Spark: UAL Creative Learning and Teaching Journal, 2(3), pp.207-216. Available at: https://sparkjournal.arts.ac.uk/index.php/spark/article/view/71 (Accessed: 25 July 2018).

Lea, M.R. and Street, B.V. (2000) ‘Student writing and staff feedback in higher education: An academic literacies approach’ in Lea, M.R. and Stierer, B. (eds.) Student writing in higher education. Buckingham: SRHE and OUP, pp.32–46.

Lockheart, J. (2017) ‘Why should art and design students write: Objectifying writing, identifying praxis’ keynote, The Theory and Practice of 'Theory and Practice' in Art and Design HE, Chelsea College of Arts, UAL, London, 17 May.

Nesi, H. and Gardner, S. (2012) Genres across the disciplines: Student writing in higher education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Panesar, L. (2017) ‘Academic support and the BAME attainment gap: Using data to challenge assumptions’, Spark: UAL Creative Learning and Teaching Journal, 2(1) pp.45–49. Available at: https://sparkjournal.arts.ac.uk/index.php/spark/article/view/43 (Accessed: 25 July 2018).

Ryle, G. (1949) The concept of mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sabri, D. (2017) Students’ experience of identity and attainment at UAL: Final year report of a 4-year longitudinal study. London: King’s College London.

Sandhu, R. (2018) ‘Should BAME be ditched as a term for black, Asian and minority ethnic people?’, BBC News, 17 May. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-43831279 (Accessed: 25 July 2018).

Singh, G. and Cowden, S. (2016) ‘Intellectuality, student attainment and the contemporary higher education system’ in Steventon, G., Cureton, D. and Clouder, L. (eds.) Student attainment in higher education: Issues, controversies and debates. Abingdon: Routledge, pp.82–97.

Thomson, P. (2018) ‘Threshold concepts in academic writing’, Patter blog, 25 February. Available at: https://patthomson.net/2018/02/26/threshold-concepts-in-academic-writing/ (Accessed: 25 July 2018).

Turner, J. (2018) On writtenness:The cultural politics of academic writing. London: Bloomsbury Academic Publishing.

University of the Arts London (2016) Retention and attainment 2015/16. Internal UAL Report. Unpublished.

University of the Arts London (2017a) Retention and attainment 2016/17. Internal UAL Report. Unpublished.

University of the Arts London (2017b) Engagement and correlation with attainment summary 2016/17. Internal UAL Academic Support Report. Unpublished.

University of the Arts London (2018) Non UK Students 2017/18 Data Summary. Internal UAL Language Centre Report. Unpublished.

University College of Cariboo (2001) Writing in the disciplines. Available at: https://www.tru.ca/disciplines/index.htm (Accessed: 25 July 2018).

Writing Purposefully in Art and Design (2003) Writing PAD primer report. Report. Unpublished.

Writing Purposefully in Art and Design (2018) Writing PAD. Available at: http://writing-pad.org/HomePage (Accessed: 25 July 2018).

Chris Lloyd is the Associate Director of Planning: Management Information in the UAL Central Planning Unit, joining the team in 2014. He is responsible for the production of student-related management information and data reporting associated with the student lifecycle - such as admissions, enrolments and quality performance measures. Chris previously worked at Goldsmiths, University of London, and the former University of Wales, Newport where he worked as a Learning Technologist which started his interest in learning and teaching approaches and the achievement of different student groups.

Alexandra Lumley is the Associate Dean of Academic Support, in the Library and Student Support Services Directorate at UAL. She developed and implemented the first Strategy for Academic Support across UAL in 2013 and provides leadership for the five teams supporting students across the university. Alex’s previous roles have included Associate Dean of Learning and Teaching at Central Saint Martins and Programme Director and teaching posts in Graphic Design at Camberwell College of Arts. Alex has long held interests in writing as a creative practice, widening participation, and the differences and commonalities between disciplines.